Readings for Fourth Sunday in Ordinary Time: Zephaniah 2:3; 3:12-13; Psalm 146:6-7, 8-9-10; 1 Corinthians 1:26-31; Matthew 5:12a

Not long ago, Bill Maher dismissed Zohran Mamdani by calling him a “straight-up communist,” as if that were the end of the conversation. No serious engagement with ideas. No discussion of wages, housing, healthcare, or workers’ rights. Just the word — used the way it has been used in this country for a century: to make people afraid and to shut down debate.

What’s striking is that this kind of reaction no longer comes only from the political right. It now comes from a whole class of well-off “liberals” who pride themselves on being socially progressive while remaining fiercely protective of the economic arrangements that benefit them.

They’ll support diversity. They’ll support tolerance. They’ll support every cultural reform that does not threaten concentrated wealth.

But the moment someone starts talking seriously about class, about exploitation, about systems that generate poverty in the middle of abundance, suddenly the conversation becomes “dangerous,” “extreme,” or “un-American.”

And that tells us something important: even liberal politics in this country has very strict limits when it comes to challenging economic power.

Which makes today’s readings deeply inconvenient — not only for conservatives, but for comfortable liberals as well.

Because Scripture is not neutral. And it is not polite.

In today’s first reading, Zephaniah tells us that God’s future is not secured by elites, but by: “a people humble and lowly… who shall take refuge in the name of the Lord.” The future belongs not to those the world considers “winners,” but to a remnant of impoverished survivors.

And the responsorial Psalm leaves no ambiguity about divine priorities:

The Lord secures justice for the oppressed, gives food to the hungry, sets captives free, protects strangers (immigrants and refugees), sustains widows and orphans, and thwarts the way of the wicked.

That is not cultural progressivism. That is economic and social judgment.

Then Paul says something that should make every “meritocracy” uncomfortable: Not many of you were wise by human standards. Not many were powerful. Not many were of noble birth.

In other words, the Church did not begin among the educated, affluent, and influential — and it was never meant to become their chaplain.

God, Paul says, deliberately chooses the weak and the lowly in order to expose how hollow our usual standards of success really are.

That is not a message designed to reassure people who are already doing quite well.

Then Jesus goes up the mountain and does something extraordinary: He does not bless hard work. He does not bless ambition. He does not bless entrepreneurship.

He blesses: the poor, the grieving, the meek (humble, gentle, non-violent) and those who hunger and thirst for justice.

And Luke strips away any remaining ambiguity: He has Jesus say directly “Blessed are you who are poor.” Not “poor in spirit” (Matthew’s version). Not “poor but virtuous.” Not “poor but patient.” Just poor.

This is not charity language. This is political language.

Jesus is announcing that God’s future does not belong to those who win under present arrangements. It belongs to those who have been pushed aside by them.

“Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit the land.” Not the landlords. Not the corporations. The meek (humble, gentle, non-violent).

Which raises an obvious question: inherit it from whom?

From those who currently control it.

That is not spiritualized poetry. That is social reversal.

And then Jesus adds: Blessed are you when they insult you and persecute you because of me.

In other words, if you stand with the poor and challenge systems that benefit the powerful, do not expect bipartisan approval. Expect mockery — including from people who otherwise think of themselves as progressive (like Bill Maher).

Because nothing makes respectable liberals more uncomfortable than the suggestion that their comfort may depend on someone else’s suffering.

Now let’s talk again about that word: “communist.”

Karl Marx was not writing self-help books for the wealthy. He was analyzing why workers who produce society’s wealth often cannot afford to live securely in it. He was naming class as a structural reality, not a personality flaw.

And the society he imagined was one marked, at least in theory, by: shared abundance, no permanent classes, and no state serving as guardian of elite interests.

Now again, Jesus is not Marx. But when Jesus speaks about the Kingdom of God, what he describes is a world where: no one hoards while others starve, no one is reduced to a disposable labor unit, no one’s worth is determined by productivity or profit.

And that is not just talk.

Acts tells us that the first Christians: held all things in common and distributed to each as any had need.

That is not symbolic. That is economic practice.

And yet, in modern American Christianity, we are told again and again that faith has nothing to say about economic structures, only about personal morality.

Which is very convenient — for those who benefit from those structures.

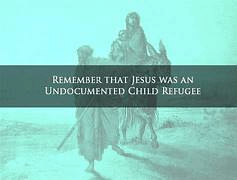

Now add one more truth we cannot afford to forget. Jesus was not only poor. He was not only from a peasant class. He was also a refugee.

Like so many at our borders today, his family fled across state lines to escape political violence. His survival depended on being welcomed as a stranger in a foreign land.

Which means that when today’s political debates treat migrants as threats, burdens, or criminals, they are not simply ignoring Jesus’ teachings — they are contradicting Jesus’ life.

Borders were not sacred and inviolable for Jesus and his family. Saving their own lives was.

And that should matter a great deal when Christians start speaking as though national security is more sacred than human dignity.

So, when I hear wealthy comedians and pundits sneer at movements for economic justice and immigrant dignity as “communist,” what I really hear is anxiety — not about ideology, but about the possibility that the moral center of society might shift away from protecting privilege.

Because let’s be honest: the Beatitudes are far more dangerous to entrenched wealth than Marx ever was.

They do not simply criticize exploitation. They declare that God’s future belongs to those who suffer under it.

And that is precisely why even “liberal” societies work so hard to tame Jesus, spiritualize his words, and turn Christianity into a religion of personal decency rather than structural transformation.

But Scripture refuses to cooperate. From the prophets to Paul to Jesus himself, the message is consistent: God sides with the poor. God challenges the powerful. God imagines a world beyond class domination and enforced scarcity.

And if that vision makes polite society nervous — if it earns ridicule from television studios and think tanks — then perhaps it is doing exactly what it is supposed to do.

Because Jesus said: Blessed are you when they insult you and persecute you

and speak evil against you falsely because of me.

And this not because suffering is good, but because standing with the poor has always been the place where God’s kingdom collides with human empires — including empires that call themselves liberal, enlightened, and even Christian.

And that collision is not behind us.

It is very much still unfolding.