If it’s true (as claimed here last week) that both Jesus and Paul proclaimed God’s Kingdom in such stark contrast to imperial Rome, how is it that by the fourth century Christianity found itself allied with Rome? Historical analysis makes it clear that the alliance was the result of the imperialization of Christianity rather than of the Christianization of empire.

To begin with, there are many indications that Jesus resisted empire specifically. Much has been written about this. However, the simplest illustration of Jesus’ opposition is in the famous story of his temptations in the desert. The story is familiar. With variations, it is contained in all four of the canonical gospels. Jesus has just been baptized by John. In Luke’s version, a voice has told him that he is somehow the “Son of God.” He goes out to the desert to discover what that might mean; he’s on a vision quest. He prays and fasts for 40 days. Afterwards come the visions of devils, angels, and of his own life’s possibilities. Satan tests him. In Matthew’s account, the culminating temptation is unmistakably imperial. It occurs on a high mountain. Satan shows Jesus all the kingdoms of the earth – an empire much vaster than Rome’s. The tempter says, “All of this can be yours, if only you bow down and worship me.” Jesus refuses. He says, “Be gone, Satan! It is written, the Lord God only shall you adore; him only shall you serve.” In other words, Jesus rejects empire in no uncertain terms. The story at the beginning of the accounts of Jesus words and deeds establishes him as anti-imperial.

That opposition to empire is extremely important to understanding what became of Christianity over 1500 years ago, when its leading faction decided to climb into bed with empire. In terms of Matthew’s temptation narrative, orthodox Christianity began worshipping Satan at that point, since in his account Satan worship was the prerequisite to reception of his “gift” of empire.

More specifically, in the 4th century, circumstances made it necessary for the emperor Constantine and his successors to repeat Satan’s temptation – this time to a cooperative faction within the leadership of the Christian church. That faction was asked to allow Christianity to become the official religion of the Roman Empire. In return church authorities would exercise a kind of co-dominion with Rome. All they had to do was accept empire, give it religious legitimacy – become the state religion. Jesus had said “no” to a similar temptation. Fourth century church leadership said “yes.” In doing so, they effectively said “yes” to Satan worship – the necessary precondition of accepting empire. They also abandoned the Jesus of history and his this-worldly message. In the process, they reduced Jesus to a mythological figure and Christianity to a Roman mystery cult. Here’s how. . . .

Like all oppressors, Constantine realized that religion represented an incomparable tool for controlling people. If an emperor can convince people that in obeying him they are obeying God, the emperor has won the day. In fact it is the job of any state religion to make people believe that God’s interests and the state’s interests are the same.

What Constantine saw in the 4th century was that Rome’s state religion was losing power. Christianity was spreading rapidly. And it was politically dangerous. The message of Jesus was particularly attractive to the lower classes. It affirmed their dignity in the clearest of terms. Often the message incited slaves and others to rebel rather than obey. Rome’s knee-jerk response had been repression and persecution. But byConstantine’s day,Rome’s repression had proved ineffective. Despite Rome’s throwing Christians to the lions for decade upon decade, the Jesus Movement was more popular than ever.

Constantine decided that if he couldn’t beat the Christians, he had to join them – or more accurately, co-opt them. And he evidently decided to do so by robbing Christianity of its revolutionary potential. He would do so, he determined, by converting the faith of Jesus into a typical Roman “mystery cult,” a form of religion that was extremely popular in 4th century Rome. Mystery cults were “salvation religions” that worshipped gods with names like Isis, Osiris, and Mithras. Mithras was particularly popular. He was the Sun God, whose feast day and birth happened to be celebrated on December 25th. Typically the “story” celebrated in mystery cults was of a god who descended from heaven, lived on earth for a while, died, rose from the dead, ascended back to heaven, and from there offered worshippers “eternal life,” in return for joining the cults. There the god’s body was eaten under the form of bread, and the god’s blood was drunk under the form of wine. The unity thus achieved assured “salvation” after death.

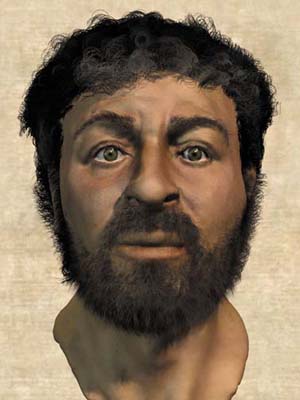

To convert Christianity into a mystery cult, Constantine (who wasn’t even a Christian at the time) convoked a church council – the Council of Nicaea in 325. There the question of the day became who was Jesus of Nazareth. Was he just a human being? Was he just a God and not a human being at all? Was he some combination of God and man? Did he have to eat? Did he have to defecate or urinate? Those were the questions. For Constantine’s purposes, the more divine and otherworldly Jesus was the better. That would make him less a threat to the emperor’s very this-worldly dominion.

The result of all the deliberations was codified in the Nicene Creed:

I believe in one God, the Father Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth, and of all things visible and invisible. And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the only-begotten Son of God, begotten of the Father before all worlds; God of God, Light of Light, very God of very God; begotten, not made, being of one substance with the Father, by whom all things were made. Who, for us men and for our salvation, came down from heaven, and was incarnate by the Holy Spirit of the virgin Mary, and was made man; and was crucified also for us under Pontius Pilate; He suffered and was buried; and the third day He rose again, according to the Scriptures; and ascended into heaven, and sits on the right hand of the Father; and He shall come again, with glory, to judge the quick and the dead; whose kingdom shall have no end. And I believe in the Holy Ghost, the Lord and Giver of Life; who proceeds from the Father and the Son; who with the Father and the Son together is worshipped and glorified; who spoke by the prophets. And I believe in one holy catholic and apostolic Church. I acknowledge one baptism for the remission of sins; and I look for the resurrection of the dead, and the life of the world to come. Amen.

In terms of understanding the imperialization of Christianity, it is important to notice here how the Creed jumps from the conception and birth of Jesus to his death and resurrection. It leaves out entirely any reference to what Jesus said and did. For all practical purposes it ignores the historical Jesus described earlier in this series. It pays attention only to a God who comes down from heaven, dies, rises, ascends back to heaven and offers eternal life to those who believe. It’s a nearly perfect reflection of “mystery cult” belief. The revolutionary potential of Jesus’ words and actions relative to justice, wealth and poverty is lost. Not only that, but subsequent to Nicaea, anyone connecting Jesus to a struggle for justice, sharing, and communal life is classified as heretical. That is, mystery cult becomes “orthodoxy.” Meanwhile, Jesus’ own proclamation of a this-worldly “reign of God” in opposition to the “reign of Caesar” becomes heresy. The same is true of Paul’s understanding of “the wisdom of God” in making the poor and despised his chosen people. In that sense, the post-Constantine, post-Nicaea church was founded not only against Paul, but against Jesus himself. Christians in league with empire have been worshipping Satan ever since.

Next week: Liberation Theology and the Left in Latin America