On Thursday, my granddaughter, Eva, left her home in Westport CT – on of our country’s most affluent towns – for a service project in Panama – which has recently returned to the news because of protests and demonstrations there against policies that Panamanians see as caused by the United States.

Eva’s project is called “Amigos,” and bills itself as following:

“Discover AMIGOS is a two-week group volunteer experience for ages 13 and 14. Travel to Panama with a group of students to learn about environmental issues like conservation preserving endangered wildlife! From exploring beaches for turtle eggs to hiking through nature reserves, you’ll earn 30 service hours. See how local youth are getting involved with issues they care about. Enjoy Panama’s unspoiled Pacific beaches and immerse yourself in the tropical forests of the Azuero Peninsula.”

In other words, despite Panama’s current problems, the trip promises to be completely (or at best rather) ahistorical and almost certainly apolitical. And why not? After all, how much should you tell 13-year-olds about what our government has done in places like Panama? Why spoil kids’ beach vacation saving turtles?

And besides, opponents of Critical Race Theory (CRT) would say that early teenagers like Eva are too young to face such harsh realities.

I disagree. So, despite anticipated objections of CRT opponents, I’ve decided to share as much as I know.

That’s because I care too much about my granddaughter to pass by this highly teachable moment. After all, Eva’s already very curious about politics and history. She’s read Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States and Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz’s An Indigenous People’s History of the United States. She also watches Amy Goodman’s “Democracy Now” every day. And we discuss all of that on long walks together (as shown here in a poem I wrote for Eva on her 13th birthday).

With all that in mind, I’ve thrown caution to the wind and have written Eva the following letter. We’ve already discussed it. And I’ve tried to answer my granddaughter’s questions about references she finds obscure.

I wonder, have I gone too far?

Dearest Eva,

I’m so proud of your plan to visit Panama as part of an early teens group going there for two weeks of service and learning. I know you’ll be doing environmental work, living with a local family, and visiting places of interest in Panama. All that makes me even prouder of you than I constantly am.

I also know, Eva, that you are making this trip with pure intention. You’re not going to Panama thinking you’re somehow conferring benefit on or “helping” your hosts. Neither are you traveling south because your parents or some church youth group persuaded you to do so. You’re not going simply because this “service project” will look good on your college applications years from now.

No. Your purpose we’ve agreed, is to continue our project of learning more about the world and how it works. You ‘re already such a good student of those things. You’ve manifested that by following through on your commitment to watching “Democracy Now” every day. Our conversations about what you (and I) have learned from Amy Goodman demonstrate your interest in understanding how the world really works. You want to know what really happened in the past, what’s going on now, and how to do your part in changing the world.

Of course, I join you in those intentions. Again, it’s what we end up talking about so often on our long walks together.

In fact, Panama is an excellent place for gathering the information that will help you grasp what’s happened in the entire Global South for the last 500 years. As Raoul Peck has shown in his film series, “Exterminate All the Brutes,” it’s been a long process characterized by white supremacy, colonization, and slaughter of non-whites.

You know from Howard Zinn that by “colonization” Peck is referring to the system of robbery whereby Europeans and North Americans have invaded countries in Latin America, Africa, and South Asia to steal the natives’ rich lands, gold, silver, minerals, oil, uranium, and other products. Such colonial and imperial theft has been going on since 1492 and is the reason why countries in Europe along with the United States, and Canada are rich, while those robbed of their land and resources by the whites are either dead or left extremely poor.

The shocking fact is that all the world’s poor countries are former colonies of Europeans and North Americans. That tells you something about the entire larcenous process I’m addressing here.

And yes, it’s all involved with white supremacy. I mean the white colonists (or imperialists) from Europe and North America typically have regarded the black and brown people in countries like Panama as inferiors, as “less than,” and even as animals to be exterminated. (I know you’re aware of all that because you’ve read that book your grandma and I gave you years ago, An Indigenous People’s History of the United States.)

So, keep what you’ve already learned in mind as you work in Panama. It represents a classic case illustrating the imperial and colonial practice of (1) Using force to steal land including entire continents and transferring the riches involved to the “Mother Country,” (2) governing the stolen countries through collaborating (usually white) puppet “presidents” who represent the country’s rich elite 10% (again, usually white) while the poor non-white majority is left in slums, poblaciónes, favelas, and impoverished barrios, (3) replacing the puppets by rigged elections or even assassination should they institute programs that actually help the countries’ poor brown and black majorities by providing benefits such as universal health care, free education, decent housing, low food prices, and guaranteed jobs. (The process of replacement is called “coup d’état” or “regime change”).

Now, think about how that process evolved in Panama. There, U.S. imperialists actually created the country out of nothing back in 1903. It was then that the Colombian government refused to sell to the U.S. the part of its country which eventually became Panama. Responding to the refusal, President Theodore Roosevelt simply sponsored a “rebellion” of secession against Colombia and immediately recognized the breakaway section as a new country (now controlled by the United States as described above).

And why was the U.S. so interested in Panama? What did it have to offer? Look at a map, and you’ll see.

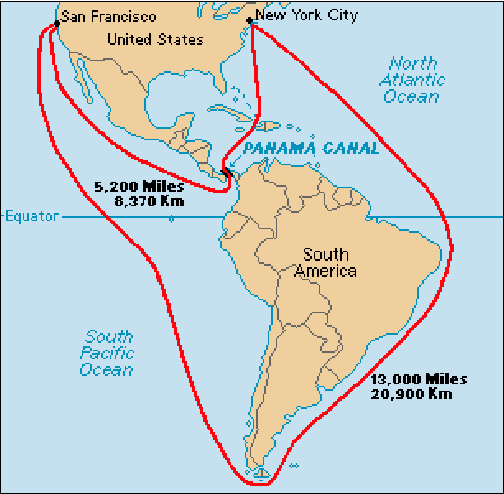

Panama happens to be located at the thinnest point between the North American continent (including Mexico and Central America). That means that it was an ideal place for digging a shipping canal that would help European and U.S. merchants, adventurers, and “gold rushers” obviate the need to sail all the way around the southern tip of South America (Tierra del Fuego) to reach California. This became extremely important after the 1849 discovery of gold there (on land btw stolen from Mexico whose Spanish colonizers (i.e., thieves) had in turn stolen it from the continent’s indigenous).

Well, the poorer people of Panama didn’t much like that. So, they often rebelled. But their uprisings were consistently defeated by the United States military which installed a large military base on the isthmus to keep the “peace” (i.e., U.S. control). The base was called Fort Sherman and was commissioned till 1999.

The United States also maintained “The School of the Americas” in Panama from 1946 until it was expelled from the country in 1984. In that year pressure from Panamanians forced its relocation to Fort Benning, Georgia. The school trained military officers from all over Latin America as a violent and often brutal insurance policy against the frequent rebellions of poor people against what they saw as exploitative U.S. control of their bodies and work.

One of those rebellions occurred in Panama in 1968. It was then that Omar Torrijos unseated a U.S. puppet and proceeded to change the country’s economy to help Panama’s long-disadvantaged lower classes. He also pressed the United States to cede ownership and control of the Panama Canal to Panamanians instead of the United States. That happened in 1999.

For his efforts, Torrijos was classified by the United States as a “dictator.” Still, because he was so popular with the Panamanian majority, he managed to remain in power till 1981 when he was killed in a plane “accident.” Insiders like John Perkins say the tragedy was engineered by the U.S. government. Perkins should know. He secretly worked for U.S. intelligence agencies (linked to the CIA) specifically charged with thwarting democratic tendencies in Latin America. His work assured continued United States control in places such as Panama. Conveniently, all CIA records about the Torrijos’ crash have somehow been lost.

Torrijos was succeeded by a long-time CIA asset called Manuel Noriega reputedly connected to the Torrijos plane crash as well as to Panama’s flourishing drug trade. But strangely, once in power, Noriega continued his predecessor’s programs aiding Panama’s poorest.

Noriega remained in power from 1983 to 1991. At that time, the United States decided Noriega had outlived his usefulness. So, he was reclassified from CIA asset and ally to a hideous drug dealer whose regime needed changing.

But how did the U.S remove Noriega from power? They bombed an entire neighborhood of Panama’s poorest who had benefitted from the Torrijos reforms. The barrio is called El Chorillo. The bombing killed at least 2000 mostly brown and black people (some say as many as 10,000) and created 15,000 homeless refugees – all, they alleged, in order to remove one man from power. Critics however say it was also intended to test new weapons systems on live people.

In any case, a subsequent “new order” in Panama restored to power the usual suspects (white affluent businessmen) who returned to the United States de facto control of the Panama Canal.

Chief among the businesses controlling Panama is Chiquita Banana (formerly called United Brands and United Fruit). Founded in Boston in 1870, it has controlled (exploited) Central America ever since. In fact, throughout Central America Chiquita is referred to as “the Octopus,” because in all the “Banana Republics” (Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Panama) the firm has its hands in everything. It controls who’s elected president and how long presidents remain in power. It controls wages, the living conditions of its workers, their education, health care, etc.

Panama is also an infamous center of high finance. It has become a tax haven for businesses from all over the world. This means that such firms can avoid paying taxes at home by “legally” setting up fictitious offices (often mere post-office boxes) as their headquarters in Panama where taxes are kept very low. All of that was confirmed in 2016 by the publication of “The Panama Papers” detailing widespread crime, corruption, and wrongdoing by Panamanians and outside investors backed by the U.S. government.

There’s so much more to say about all of this, dear Eva. But this will have to do for now. If you want more, you should read John Perkins’ Confessions of an Economic Hit Man, and/ or The American Trajectory Divine or Demonic? by Process Theology’s David Ray Griffin (pages 328-332), and/or Jonathan Katz’s Gangsters of Capitalism (chapter nine).

With all of this in mind, as you get the opportunity, please ask your teachers and guides in Panama about these matters. You might also share these insights with any friends you happen to make there in your Amigos group.

But I’ll bet you this: even the leaders of your adventure probably won’t know this story in as much detail as I’ve shared with you. Panama’s history (and history in general) is way more complicated and shocking than our “teachers” are willing to admit. They’ll never tell you that “our” wealth has been based on the transfer of resources from the world’s poor to the coffers of largely white bankers and businessmen. They’ll never admit that the United States has been an unrelenting force of hardship and oppression in the Global South. They’ll never tell you the unvarnished history of countries like Panama.

But now you know the rest of the story. You’re now in position to employ your sharp research skills to first of all check out the veracity of what I’ve shared here. Then having done so, you can ask questions and weigh the “experts’” responses.

Needless to say, I look forward to our discussing all of this and your experience when you return home in a couple of weeks.

Till then, have a great time in Panama. Make friends. Keep your eyes open. And if you can, visit El Chorillo. That would be much more interesting than the tour I’m sure they have planned for you.

With great love,

Baba