Readings for the first Sunday of Lent: Genesis 2: 7-9, 3: 1-7; Psalm 51: 3-6,12-13, 17; Romans 5: 12-19; Matthew 4: 1-11.

Today is the first Sunday of Lent. Its readings begin with the creation myth in Genesis. They conclude with the famous story of Jesus’ temptations in the desert.

But let me begin not in Eden or in the wilderness, but in Washington, Brussels, and Tel Aviv — and in the shadow places of our own national story.

We live in a country that represents roughly 4.5 percent of the world’s population yet assumes a decisive voice in nearly every corner of the globe. We maintain military installations across continents. We speak of “rules-based international order” while reserving to ourselves the authority to determine when rules apply.

The war in Ukraine grinds on amid NATO expansion despite promises to the contrary. Gaza has become a landscape of genocide even as our government supplies arms and diplomatic cover.

Regime-change interventions in Iraq, Libya, and Afghanistan have left instability that outlives the speeches that justified them. And at home, the Epstein scandal remains a symbol of elite circles that appear shielded from consequences that would crush ordinary people.

Whatever one’s political alignment, it is difficult to deny that we inhabit an imperial moment.

That is why the Gospel today matters. Because the final temptation Jesus faces is not about private morality. It is about his rejection of empire.

How Animals Became Human

But before we get to the desert, we must pass through Genesis. And Genesis is stranger than we usually allow. It’s a sacred myth about how the animals became human.

Nonetheless, we were taught — many of us in catechism classrooms that did not encourage too many questions — that this story explains how a perfect world fell apart because of disobedience. But biblical scholarship has long suggested something more subtle and more interesting. The story reads less like a fall from perfection and more like the painful emergence of moral consciousness.

God forms the human being from the soil — adamah — and breathes into it. The human is an earth creature animated by divine breath. The animals are already there. What distinguishes this creature is not biology but awareness.

The serpent does not tempt with gluttony. The fruit is “desirable for gaining wisdom.” The promise is that “you will be like gods, knowing good and evil.” The issue is not appetite; it is autonomy. It is the claim to define good and evil independently of the Giver of breath.

And here is where the text becomes theologically uncomfortable. The God portrayed in Genesis can sound petty and jealous. (In fact, as biblical scholars Mauro Biligno and Paul Wallis have suggested, the plural Elohim in today’s reading might not refer to God at all, but to “Powerful Ones” pretending to divine identity. But that’s another story.) In any case, the prohibition from on high appears arbitrary. The threat — “you shall die” — sounds disproportionate. If we read the story naïvely, we are left with a deity who seems insecure about competition.

Many Christians resolve that discomfort by refusing to wrestle with the text. We flatten it. We moralize it. We turn it into a children’s story about disobedience and punishment. That is the fundamentalism many of us were raised on — including in Catholic form — a fundamentalism that often ignores biblical scholarship and historical context in favor of simple certainty.

But the deeper issue in Genesis is not that God fears competition. It is that humans actually do become like God. In the end the Powerful Ones (Elohim) admit “The man has now become like one of us, knowing good and evil.” However, the moment the earth creature claims ultimate moral sovereignty, alienation follows. Shame. Blame. Fear. Violence. The story is mythic, but it describes something real: despite God-like powers, when creatures enthrone themselves as divine, relationships fracture.

The serpent’s whisper — “you will be like gods” — does not remain in the garden. It scales upward into civilizations.

Empires are what happen when that whisper becomes policy.

Jesus’ Temptations in the Desert

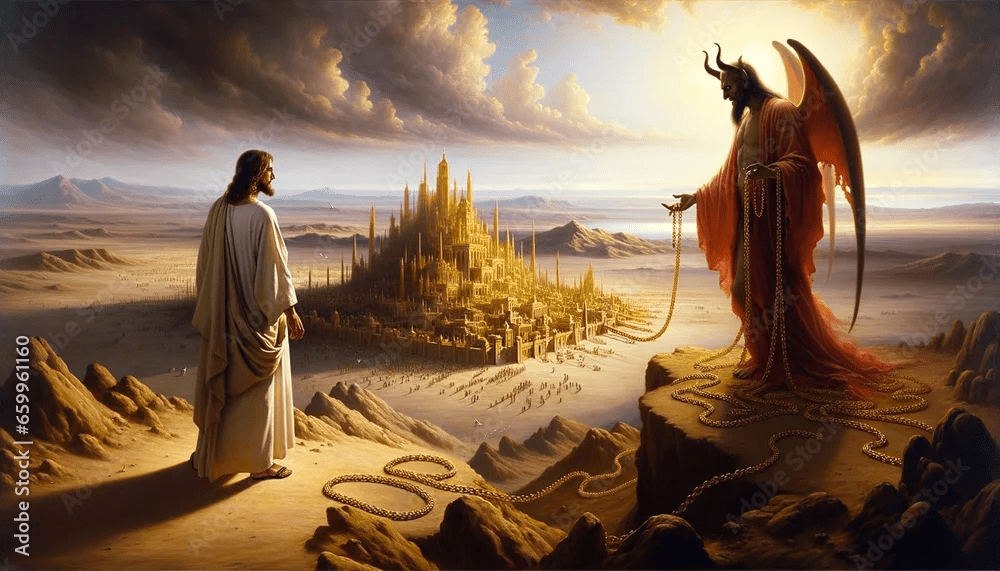

Which brings us to the desert. Matthew tells us that Jesus is led by the Spirit into the wilderness to be tempted. The temptations escalate. First, appetite: turn stones into bread. Reduce humanity to consumption. Then spectacle: throw yourself from the temple and force divine validation. Manipulate religion to secure legitimacy. And finally, the decisive offer: all the kingdoms of the world and their magnificence — in exchange for worship.

This is the climax. Empire is offered as destiny.

And here the contrast with Genesis becomes luminous. The first humans grasp at godlike autonomy. Jesus refuses it. He refuses to reduce life to bread. He refuses to weaponize God. And he refuses political domination secured by kneeling before a lesser power.

“The Lord your God shall you worship, and him alone shall you serve.”

That sentence is not pious abstraction. It is a political declaration. It means that no nation, no military alliance, no economic system, no leader can claim ultimate allegiance. It means that empire — however benevolent it imagines itself — is not God.

This is precisely where much contemporary Christianity falters. Christian fundamentalism, whether Protestant or Catholic, often aligns itself enthusiastically with imperial power. It baptizes national projects. It equates military strength with divine blessing. It reads Scripture in a way that reinforces dominance rather than questions it. The same tradition that once rejected liberation theology for being “too political” now blesses drones, sanctions, and occupation without hesitation.

And yet the Gospel we read today shows Jesus rejecting the very thing many Christians defend.

He rejects empire as diabolical.

Paul & Psalms

Paul’s letter to the Romans reframes the story. Through one human being came sin — the pattern of grasping autonomy. Through another came obedience — the pattern of trust. The contrast is not between sexuality and purity, or rule-breaking and rule-keeping. It is between self-deification and worship.

Psalm 51’s cry — “Create in me a clean heart” — becomes, in this context, a plea for undivided allegiance. A clean heart is not one that never doubts. It is one that refuses to kneel before false gods.

Lenten Conclusion

Lent, then, is not about chocolate or minor self-denials. It is about allegiance. It is about whether we will continue participating in systems that assume the right to dominate the earth and dictate history — or whether we will align ourselves with the one who refused.

If Genesis tells the story of animals becoming human through moral awareness, the desert tells the story of a human refusing to become a god.

And that refusal leads to a cross, because empire does not tolerate rivals or dissent.

We begin Lent in a world intoxicated with power. The kingdoms are still on offer. They are offered to nations. They are offered to churches. They are offered to each of us in smaller ways — security in exchange for silence, comfort in exchange for complicity.

The question is not whether temptation exists. The question is before whom we will kneel.

Dust breathed upon by God does not need to become divine. It needs only to remain faithful.

And that, perhaps, is the most subversive act of all.