Last week Peggy and I received the very sad news that our long-time friend, John Capillo, had died suddenly on New Year’s Eve. Mercifully, there was no long illness. Stomach pains brought him to the emergency room. He was diagnosed with pneumonia, suffered septic shock, and suddenly was gone. He was 76 years of age.

For us, it was John’s second death. Years ago, Peggy and I said goodbye to him as he lay in coma in a Lexington (KY) hospital. We laid hands on him as we left his bedside then and thanked him for all his gifts to us and the world. But afterwards the unexpected happened. He was given a reprieve; he came back from the dead to live among us for several more years. It seemed entirely miraculous.

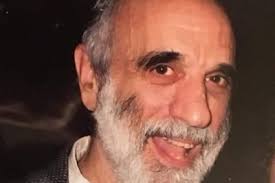

In any case, this time it’s final. And our world won’t be the same without this extraordinary man. He was a priest, a prophet, a teacher, storyteller, and a social justice warrior of astonishing accomplishment.

I first met John Capillo 40 years ago, when he and Terri and their new baby, Maureen, moved to Berea, Kentucky. One Sunday, the three of them showed up for Mass at St. Clare’s Church, where Peggy and I had been parishioners since our own arrival in town 5 years earlier. By then, we had our own daughter, Maggie, who was just about Maureen’s age.

Immediately, I learned that, like me, John had been a priest – ordained in New York’s Brooklyn archdiocese. That did it: we soon became fast friends – as did Maggie and Maureen. Peggy and Terri also shared a deep friendship.

At the beginning, John’s day job was carpentry. He had learned the trade during his first priestly assignment in Puerto Rico (or was it Guatemala? I forget.) John had showed up there to help rebuild after a hurricane or something. However, (as he told me early on) when he declared his do-good intention, an old man took him aside and said, “Padre, we know how to build houses. We need you to be our priest.”

And so, John did just that with the enthusiasm, commitment and insight that characterized his entire life. However, his desire to make the gospel relevant moved him to take chances with liturgy and edgy homilies that rendered him suspect to his superiors. The resulting conflicts with authority eventually drove him from the priesthood and into family life.

Nevertheless, John never did give up carpentry or building. One Sunday shortly after arriving in Berea, he came to Sunday Mass with bandages on his left hand. The previous week, he had cut off a finger with his Skill Saw.

Undeterred, at one point, he built a solar addition onto our house in Buffalo Holler about 5 miles outside Berea’s city limits. The project was designed by Appalachian Science in the Public interest. It caught John’s imagination, because, like Peggy and me, he and Terri were going through a “back to nature” phase. He thrived on environmental harmony, innovation, recycling and simple living.

In fact, years later John built an even more innovative structure for himself. It was made entirely from strong woven-plastic bags filled with dirt. John had done a study on the process and technology. And soon he was filling the required bags and carefully laying out the building’s perimeter. Layer after layer created outside walls, interior divisions, and then a roof.

Everything was laid out carefully to take advantage of the sun, but also to orient the house towards sacred energies John perceived as housed in the east, north, west, and south. He wanted to steep himself deeply in such emanations, even while asleep. The whole project expressed John’s deep and never-abandoned desire for enlightenment and unity with God.

Yes, I saw John as a kind of saint. He was. I’ve met few people like him – always on point, never caught up in trivialities, deeply interested in meaning, and counter-cultural to a fault. That’s the way prophets are.

That’s the way John was. He cared little about externals. His diet was simple; he always ate what was set before him. He didn’t drink liquor. His beard was scruffy, his hair unkempt, his clothes always nondescript. But his soul was absolutely luminescent. His laugh was raucous and full of joy. His loud Ha-Ha’s punctuated every story he ever told.

And he told many. In fact, he considered storytelling his calling and avocation. He studied its technique. And he always used that skill to talk about things that matter – as explained in the books he devoured as the voracious reader he was. John was an inveterate book clubber. He also read my blog, commented on it often, and frequently had us talking shop at Berea Coffee and Tea. Conversations always revolved around God, politics, philosophy and family.

But John was no armchair philosopher. He was a fierce activist on behalf of El Salvador during Central America’s troubled 1980s. As he put it, he “went to school” there – learning from the people during his frequent visits about the destructive role U.S. policy played not only in Salvador, but throughout the colonial world of Latin America, Africa, and South Asia.

John was a deeply, deeply critical thinker. At one point, he spent a month in El Salvador with Peggy and her class of Berea College students as they worked with local residents struggling to overcome the disastrous effects of U.S. policy.

John’s greatest activist accomplishments came after he joined our mutual friend, Craig Williams’ Kentucky Environmental Foundation (KEF). It was and remains a grassroots organization committed to environmental justice. KEF’s main focus became delivering Berea’s Madison County from arrogant U.S. Army plans to dispose of World War II chemical weapons containing mustard gas and other genocidal poisons. The Army had planned to simply burn it all in a thoughtless incinerator near our homes, schools and local businesses.

However, with John’s help, KEF stopped the planners in their tracks. KEF mobilized the entire county and state to prevent that particular disaster from happening. It actually defeated the U.S. Army! Eventually, KEF linked up with similarly victimized communities throughout the United States and the world to work for and celebrate analogous accomplishments.

It was all truly heroic. And John was a huge part of all that. For years, KEF was his final regular job. And in that capacity, he mentored numerous Berea College students including our own daughter, Maggie, who had the privilege of working closely with him and Craig as a student-volunteer.

Here’s a list of some other ways I experienced John as activist, prophet, teacher, and friend:

- Any of us organizers and educators could always count on John to attend and participate in meetings of any kind, anywhere if they addressed issues of spirituality, activism, critical thinking and/or critical living.

- He was an advocate and friend of Berea’s and Madison County’s large Hispanic community often working as a translator for its members in court and in social services offices.

- He was a frequent guest in my own (and Peggy’s) Berea College classes where he edified and provoked students with his informative stories and explanations about our country’s Central American wars and about the environmental dangers of incineration. He was so effective with students.

- For years, John was a faithful and active member of the Berea Interfaith Task Force for Peace, which during the ‘80s was organized around nuclear disarmament and opposition to our government’s tragic interventionism in Nicaragua and El Salvador.

- One January, the two of us taught a month-long Berea College course on environmental justice. The course took place in Alabama, where another U.S. Army incinerator threatened the local mostly African American community. The offering was called “Taking on the Military Industrial Complex.” You can imagine the conversations John and I had in the process.

- Years later, John joined Peggy and me in Oaxaca for a month-long course with Mexico’s Gustavo Esteva — himself an extraordinary critical thinker – who deeply influenced so many of us through his seminars, lectures, prophetic example and books like Grassroots Postmodernism. John loved Gustavo.

- John was there for me when I tried to start a home church.

- He visited me at our lake house in Michigan last summer. We spent the entire afternoon on our back porch talking of our usual things – family, politics, church, theology, books. John was extraordinarily proud of his four children and of his grandchildren. I treasure that memory.

As I said, John Capillo was a saint. He was one of my closest friends. Unfortunately, he won’t be coming back from the dead this time (physically, that is). Peggy, Maggie and I will miss him. The world is poorer for his absence.