Readings for 14th Sunday in Ordinary Time: Is. 66: 10-14c; Ps. 66: 1-7, 16, 20; Gal. 6: 14-15; Lk. 10: 1-12, 17-20. http://www.usccb.org/bible/readings/070713.cfm

Sometimes I wonder if I’m on the right path. Do you ever think that about yourself? I’m talking about wondering if your whole “take” on the world is somehow off base.

My own self-questioning has been intensified by my blogging over the last 15 months. For instance I recently wrote a piece on why I refused to celebrate the 4th of July. My thesis was that the U.S. has lost its way, turned the Constitution into a dead letter, and made its claims to democracy meaningless. We are rapidly moving, I said, in the direction of Nazi Germany. All of that is contrary to the Spirit of 1776. So there’s no point in celebrating Independence Day as if Edward Snowden and Bradley Manning didn’t exist.

One person kind enough to comment said she lost all respect for me as a result of what I had written. Others have told me that my message is just a poor man’s left-wing version of the ideological nonsense spouted by Sean Hannity and Rush Limbaugh. Even people close to me have referred to what I write as diatribes, screeds, and rants. I hope that’s not true.

What is true is that as a theologian, I’m attempting to write “About Things That Matter” (as my blog title puts it) from a self-consciously progressive (i.e. non-conservative) perspective – or rather from a theological perspective that recognizes that following Jesus is counter-cultural and requires a “preferential option for the poor” — not the option for the rich that “America” and its right wing versions of Christianity embrace.

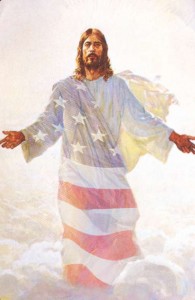

I adopt this position in a national context that I recognize as anti-gospel – materialistic, individualistic, extremely violent, and pleasure-oriented. Or as my meditation teacher Eknath Easwaran says, our culture refuses to recognize that we are fundamentally spiritual beings united by the divine core we all share. At heart, we are 99% the same in a culture that tells us we’re 100% unique. Jesus’ values are not the American values of profit, pleasure, power, and prestige.

Instead what Yeshua held as important is centered around the Kingdom of God – a this-worldly reality that turns the values of this world on their head. The Kingdom embodies a utopian vision that prioritizes the welfare of the poor and understands that the extreme wealth Americans admire is a sure sign that those who possess it have somehow robbed others of their due.

As a possessor of extreme wealth myself (on a world-scale) each time I read the gospels – or the newspaper – I feel extreme discomfort. In other words, it’s Jesus’ Gospel that makes me think I’m on the wrong track. But it’s not the one critics have in mind when they suggest I temper my positions.

Instead, consideration of Jesus’ words and deeds convince me that I’m not radical enough. I do not yet occupy a position on the political spectrum respectful enough of the poor. I’ve forgotten that life outside God’s Kingdom (“Jerusalem”) is “Exile” in God’s eyes (as today’s first reading recalls). The liberation from slavery referenced in this morning’s responsorial psalm has lost its central place in my spirituality.

Our culture might say, that by all this I mean that I’m not far enough “left.” Be that as it may. The truth is that insofar as my daily life doesn’t reflect Jesus’ utopian values, I should feel uncomfortable.

Today’s second and third readings reinforce my discomfort. They highlight the conflict between the values of Jesus and those of “the world” – of American culture in our case. In fact, the world finds it hard to understand Jesus’ real followers at all. And why not? For all practical purposes, our culture denies the very existence and /or relevance of spirituality to everyday life – at least outside the realm of the personal.

In today’s excerpt from his Letter to Galatia, Paul says the world considers the Christian life not even worth living. That’s what Paul means when he says that in Christ he is crucified to the world (i.e. in the world’s opinion). He means that as far as the world is concerned, he as a follower of Jesus is already dead because of his rebellion against the values of Rome. Crucifixion, after all, was the form of torture and capital punishment reserved for insurgents against the Empire.

But then Paul turns that perception on its head. He writes that his accusers are wrong. In reality, it is life lived according to Roman values that is not worth living. Paul says, “As far as I’m concerned, the world has been crucified.” He means that what Rome considers life is really death – a dead end. It constitutes rebellion against God’s Kingdom, the antithesis of Rome.

In today’s Gospel selection Jesus describes the lifestyle of those committed to God’s Kingdom. He sends out 72 community organizers to work on behalf of the Kingdom giving specific instructions on how to conduct themselves. They are to travel in pairs, not as individuals. (Companionship is evidently important to Jesus.) Theirs is to be a message of peace. “Let your first words be ‘peace’ in any location you frequent,” he says. He tells his followers to travel without money, suitcase or even shoes. He urges them to live poorly moving in with hospitable families and developing deep relationships there (not moving from house to house). They are to earn their bread by curing illness and preaching the inevitability of God’s Kingdom which the world routinely rejects as unrealistic.

Jesus’ followers are to spread the word that the world can be different. God should be in charge, not Caesar. Empire is evil in God’s eyes. So peace should replace anger and violence; health should supplant sickness; shared food and drink should eliminate hunger. Those are Jesus’ Kingdom values.

And the world rejects them. Not only that, Jesus’ “lambs among wolves” imagery recognizes that the world embodies an aggressive hostility towards followers of Jesus. It would devour them – so different are its values from the Master’s.

So maybe it shouldn’t surprise any of us when we’re accused of being extreme – as communists or utopians or hippies – if we’re attempting to adopt the values of Jesus.

After all, they thought Jesus was crazy. They thought he had lost his faith. They considered him a terrorist and an insurgent.

Then in the fourth century, Rome co-opted Jesus’ message. Ever since then, we’ve tamed the Master.

As our culture would have it, Jesus would have no trouble celebrating July 4th.

Am I mistaken?

![ash-wednesday-1[1]](https://mikerivageseul.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/ash-wednesday-11.jpg?w=270&h=300)