This is the first in a series on critical thinking. Its immediate inspiration was the controversy on this blog site sparked by my April 16th entry on the Boston Marathon bombing (see below on this site). Many of the most critical responses showed that their authors did not understand where I was coming from in terms of my own remarks about severity and the “blowback” nature of the tragedy in Boston. I had written that the Boston tragedy was minor compared to the havoc wrought virtually every day in the Muslim world by U.S. drone attacks. Moreover those attacks by U.S. weapons of mass destruction evoked anger and desire for revenge on the parts of their victims. So “Americans,” I suggested, should expect more tragedies like Boston.

In truth, my point of departure was not (as some critics alleged or implied) anti-Americanism or insensitive gloating over the sufferings of the Marathon victims. Far from it, I love the United States; it is my place of birth; I consider myself highly patriotic. Like most people in the world, my heart went out to the dead, maimed and injured in Boylston Square.

However, I am also a teacher of critical thinking and have been for more than 40 years. During that time I’ve developed criteria – 10 of them – for thinking critically about history, politics, economics and religion. For me the essence of critical thought entails the ability to judge oneself (and one’s country) as objectively as possible (i.e. without ego-centrism or ethnocentrism). To that end, the criteria I’ve developed include

1. REFLECT SYSTEMICALLY

2. EXPECT CHALLENGE

3. REJECT NEUTRALITY

4. SUSPECT IDEOLOGY

5. RESPECT HISTORY

6. INSPECT SCIENTIFICALLY

7. QUADRA-SECT VIOLENCE

8. CONNECT WITH YOUR DEEPEST SELF

9. DETECT SILENCES

10. COLLECT CONCLUSIONS

As anyone can see, such criteria are not those one ordinarily finds in critical thinking textbooks – at least not those historically employed at Berea College where I taught for more than 36 years. Standard approaches provide tools for analyzing the thinking process itself. They instruct students in logic, common fallacies, and how to evaluate statements, evidence, statistics and information. Diagrams used to illustrate this understanding of critical thinking often look like the following:

In many ways “thinking about thinking” accurately describes the project pictured above. According to this understanding, thinking critically is about thought processes and their logic. Once articulated and clarified, the new understandings are applied to cases such as abortion, capital punishment, immigration, and war. Without doubt, this understanding of the discipline is valuable and necessary for any serious scholarship or indeed for responsible citizenship.

However, the problem with this kind of thinking is that it can ignore questioning its own “parameters of perception.” It can work within cultural, institutional and ideological premises that largely remain unquestioned. It can proceed quite successfully without seriously questioning or even acknowledging the possibility of alternatives to existing ideologies, laws, institutions, power relationships, and customs. One can think about the Marathon bombing, for instance, without considering the accuracy of one’s accepted historical narrative about the role of the United States in the world or about the “institutional violence” that might have provoked the atrocity.

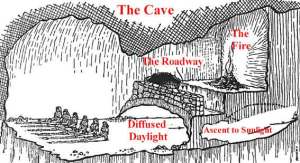

By way of contrast, critical thinking as explored in this series will address such neglected elements. The operative image here will be Plato’s Cave. Its representation looks like this:

About 2500 years ago Plato described the human condition as characterized by a tragic absence of critical thought as I’m proposing it here. We live, Plato said, like people in a cave where they’ve been imprisoned all their lives. They remain there chained in a way that prevents them from moving about. They face a wall unable to move even to see directly the others who like them are chained alongside. However the wall the prisoners face is not blank. This is because a fire burns behind the captives and casts their shadows on the wall much as a movie projector would in a dark theater. And that’s their only image of themselves – shadows.

However other shadows appear on the wall as well. They are cast by people walking behind the prisoners along the “roadway” pictured above. The walkers carry statues of all kinds of things – animals, trees, gods . . . . Viewing those shadows, the prisoners think that life is unfolding before them. Moreover, the “wise” among the prisoners – the teachers – become very good at describing the shadows and at predicting the sequence of their appearance. In terms relevant here, their discourses are taken as expressions of “critical thought.” However, their wisdom describes shadows in an artificial world.

Eventually one of the prisoners escapes the cave and discovers the real world and the sun which makes life possible. The escapee returns to the cave to inform the prisoners of this discovery. The escapee’s intention is to introduce real “criticism.” Far from welcoming him, the other prisoners threaten to kill him.

Plato, of course, was writing about his mentor, Socrates whom the citizens of 5th century BCE Athens actually did kill for teaching what I’m calling here “critical thinking.” They interpreted his project as “corrupting the youth,” because it called into question the “doxa” of their day. The Greek term, doxa, referred to the “of course” statements that go unquestioned everywhere. Our culture is full of them: “The United States” is the best country in the world.” Of course it is! “Ours is the highest standard of living.” Of course! “’We’ are good; ‘they’ are evil.” Of course!

The critical thinking I intend to pursue here is about critiquing doxa; it’s about questioning parameters of perception; it’s about escaping the cave.

More specifically, what I intend to expose here attempts to provide tools for subjecting society’s underlying narratives, along with its economic and political structures and ideologies to careful yet easily accessible analysis. Moreover, it starts not from a place of supposed neutrality, but from a place of commitment to a world with room for everyone. Commitment in one form or another is inescapable.

Consequently this approach to critical thought not only analyzes reasons for such commitment; it evaluates as well ideologies that contradict that vision. This approach will be historical and involve examination of “official” and “competing” narratives about the past. It will treat violence as a multi-dimensional phenomenon connected with structures of political economy, the struggle for survival, and police enforcement of “rules of the game” that benefit some and hurt others. The approach centralized here will give key importance to spirituality and the clear articulation of conclusions about the world and the historical patterns at work there.

My approach will also recognize that some of the best and most engaging stimuli for critical thought are can be found in popular culture’s most powerful and engaging medium, Hollywood film, as well as from outstanding documentaries. So most blog entries on this topic will include film illustration.

My hope is that readers will find these Wednesday blog entries interesting and helpful and worthy of their “critical” feedback.