Readings for Ascension Sunday: Acts 1: 1-11; Ps. 47: 2-3, 6-9; Eph. 1: 17-23; Lk. 24: 48-53

This is Ascension Sunday. For us Catholics, it used to be “Ascension Thursday.” It was a “holy day of obligation.” That phrase meant that Catholics were obliged to attend Mass on Thursday just as they were on Sunday. To miss Mass on such a day was to commit a “mortal sin.” And that meant that if you died before “going to confession,” you would be condemned to hell for all eternity.

So until the years following the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) Catholics would fill their churches on Ascension Thursday in the same numbers (and under the same threat) that made them come to Mass on Sundays. That’s hard to imagine today.

I suppose that difficulty is responsible for the transfer of the commemoration of Jesus’ “ascension into heaven” from Thursday to Sunday. I mean it wasn’t that the church changed its teaching about “holy days of obligation.” It didn’t. Catholics simply voted with their feet. They stopped believing that God would send them to hell for missing Mass on Ascension Thursday or the feast of the Blessed Virgin’s Assumption (August 15th), or All Saints Day (November 1st) or on any of the other “holy days.” Church once a week was about as much as the hierarchy could expect.

But even there, Catholics stopped believing that God would punish them for missing Mass on Sunday. So these days they more easily attend to other matters on Sunday too. They set up an early tee time or go for a hike in the woods. Afterwards they cut the lawn or go shopping at Wal-Mart. That kind of “servile work on Sundays” or shopping used to be forbidden “under pain of sin” as well. And once again, it isn’t church teaching that has changed. Catholics have just decided that the teachings don’t make sense anymore, and have stopped observing them.

And apparently they do so in good conscience. So you won’t find them running to confession after missing Mass or working and shopping on Sunday. In fact, that’s another way Catholics have voted with their feet. For all practical purposes, they’ve stopped believing in Confession – and largely in many of the mortal sins they were told would send them to hell – like practicing contraception or even getting a divorce.

I remember Saturday evenings when I was a kid (and later on when I was a priest). People would line up from 4:00-6:00, and then from 7:00 -9:00 to “go to Confession.” And the traffic would be steady; the lines were long. No more! In fact, I personally can’t remember the last time I went to confession. And no priests today sit in the confessional box on Saturday afternoons and evenings waiting for penitents to present themselves.

What I’m saying is that the last fifty years have witnessed a tremendous change in faith – at least among Catholics. Our old faith has gone the way of St. Christopher and St. Philomena and “limbo” all of which have been officially decertified since Vatican II.

In fact, since then the whole purpose of being a Catholic (Christianity) has become questioned at the grassroots level. More and more of our children abandon a faith that often seems fantastic, childish and out-of-touch. Was Jesus really about going to heaven and avoiding hell? Or is faith about trying to follow the “Way” of Jesus in this life with a view to making the world more habitable for and hospitable to actually living human beings?

That question is centralized in today’s liturgy of the word. There the attentive reader can discern a conflict brewing. On the one side there’s textual evidence of belief within the early church that following Jesus entails focus on justice in this world – on the kingdom. And on the other side there are the seeds of those ideas that it’s all about the promise of “heaven” with the threat of hell at least implicit. The problem is that the narrative in today’s liturgy of the word is mixed with its alternative.

According the story about following Jesus as a matter of this-worldly justice, the risen Master spent the 40 days following his resurrection instructing his disciples specifically about “the Kingdom.” For Jews that meant discourse about what the world would be like if God were king instead of Caesar. Jesus’ teaching must have been strong. I mean why else in Jesus’ final minutes with his friends, and after 40 days of instruction about the kingdom would they pose the question, “Is it now that you’ll restore the kingdom to Israel?” That’s a political and revolutionary question about driving the Romans out of the country.

Moreover Jesus doesn’t disabuse his friends of their notion as though they didn’t get his point. Instead he replies in effect, “Don’t ask about precise times; just go back to Jerusalem and wait for my Spirit to come.” That Spirit will “clothe you in justice,” he tells them. Then he takes his leave.

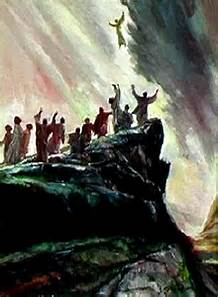

Presently two men clothed in white (the color of martyrdom) tell the disciples to stop looking up to heaven as if Jesus were there. He’s not to be found “up there,” they seem to say. Jesus will soon be found “down here.” There’s going to be a Second Coming. Jesus will complete the project his crucifixion cut short – restoring Israel’s kingdom. So the disciples who are Jews who think they’ve found the Messiah in Jesus return in joy to Jerusalem and (as good Jews) spend most of their time in the Temple praising God, and waiting to be “clothed in Jesus’ Spirit” of liberation from Roman rule.

The other story (which historically has swallowed up the first) emphasizes God “up there,” and our going to him after death. It’s woven into the fabric of today’s readings too. Here Jesus doesn’t finally discourse about God’s kingdom, but about “the forgiveness of sin.” After doing so, he’s lifted up into the sky. There Paul tells his readers in Ephesus, he’s enthroned at the Father’s right hand surrounded by angelic “Thrones” and “Dominions.” This Jesus has founded a “church,” – a new religion; and he is the head of the church, which is his body.

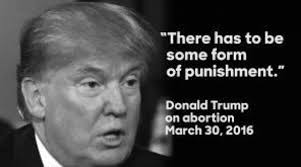

This is the story that emerged when Paul tried to make Jesus relevant to gentiles – to non-Jews who were part of the Roman Empire, and who couldn’t relate to a messiah bent on replacing Rome with a world order characterized by God’s justice for a captive people. So it gradually turned Jesus into a “salvation messiah” familiar to Romans. This messiah offered happiness beyond the grave rather than liberation from empire. It centralized a Jesus whose morality reflected the ethic of empire: “obey or be punished.” That’s the ethic we Catholics grew up with and that former and would-be believers find increasingly incredible, and increasingly irrelevant to our 21st century world.

Would all of that incredibility and irrelevance change if the world’s 2.1 billion Christians (about 1/3 of the world’s total population) adopted the this-worldly Jesus as its own instead of the Jesus “up there?” That is, would it change if Christians stopped looking up to heaven and focused instead on the historical Jesus so concerned with God’s New World Order of justice for the poor and rejection of empire?

Imagine if believers uncompromisingly opposed empire and its excesses – if what set them apart was their refusal to fight in empires wars or serve its interests. How different – and more peaceful – our world would be!

A sensitive discerning reading of today’s liturgy of the word, a sensitive and critical understanding of Jesus’ “ascension” presents us with that challenge. How should we respond?

(Discussion follows.)