Readings for 3rd Sunday of Lent: Ex. 3:1-8A, 13-15; Ps. 103: 1-4, 6-8, 11; I Cor. 10:1-6, 10-12; Lk. 13: 1-9 http://www.usccb.org/bible/readings/030313-third-sunday-lent.cfm

I’m currently teaching a little Lenten seminar on the historical Jesus. Its central emphasis explores the context of Jesus life and words. The idea is that understanding that context will help us better interpret the gospel readings we encounter in church each Sunday. Our goal is to get closer to the meaning intended by the Four Evangelists and beyond that by the historical Jesus who stands behind the evangelists’ interpretations of the carpenter from Nazareth.

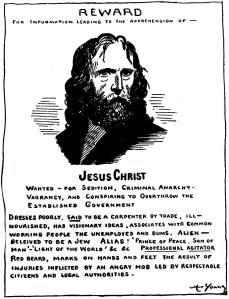

We’ve discovered that one of the criteria for identifying the authentic words and deeds of Jesus is the unconventionality of Jesus’ teaching. By all the accounts we find in the gospels, Jesus regularly scandalized and angered his straight-laced listeners – especially the professional rabbis, priests and scribes. So anything in the gospels that smacks of the scandalous has a point in its favor regarding the authenticity that concerns our seminar. By the same token, expressions of conventional wisdom are doubtfully authentic for that very reason.

With this in mind, there are at least two ways of interpreting today’s gospel reading from Luke. The more or less standard reading boils down to conventional wisdom. It’s what we usually hear from the pulpit. The other interpretation is truer to Jesus’ context. The difference between the two interpretations illustrates what we’re about in the seminar I mentioned. Contrasting the understandings also uncovers a strong challenge otherwise concealed in this more contextualized reading.

Before we get to that, consider the standard interpretation of this text. Jesus is asked about “the Galileans whose blood Pilate had mingled with the blood of their sacrifices.” Evidently, Roman soldiers had surprised some Galilean insurgents while the rebels were engaged in worship. The soldiers had slaughtered the men then and there. Jesus asks “Do you think that because these Galileans suffered in this way because they were greater sinners than all other Galileans?” Then he answers his own question, “By no means! But I tell you, if you do not repent, you will all perish as they did!”

Jesus continues his questioning. He asks,

“Or those eighteen people who were killed

when the tower at Siloam fell on them—

do you think they were more guilty

than everyone else who lived in Jerusalem?

By no means!

But I tell you, if you do not repent,

you will all perish as they did!”

Here interpreters unfamiliar with the historical context in question usually understand Jesus as referring to a random accident that was well-known in his time. A tower had fallen by chance and killed some innocents. It raised the familiar question, “Why do bad things happen to good people?”

In both cases, Jesus’ answer seems to be: bad things happen to good people because the people aren’t really good. The insurgents were guilty and deserved what they got. The same is true about the apparently innocent bystanders killed by the tower’s freak accident. Even more, Jesus seems to be saying, everyone is guilty and needs to repent or all will perish in the same way. “Repentance” is usually understood as more faithful observance of the 10 Commandments – especially those having to do with sex.

There are obvious problems with this interpretation. To begin with, the “wisdom” attributed to Jesus is nothing if not “conventional.” That in itself distances the explanation from the decidedly unconventional historical Jesus. Secondly, the standard interpretation ignores the political nature of this passage. It places in the same category of “acts of God” the accidental collapse of a tower on the one hand and the murder of Jewish patriots on the other. This equivalency has Jesus more or less endorsing Pilate as the agent of God’s punishment for the sins of the Galileans in question. Such endorsement and lack of political nuance is hard to imagine coming from the mouth of a Galilean Jew of the 1st century.

An explanation more faithful to Jesus’ context takes the topic of today’s readings to be violence, counter-violence and the need for non-violent resistance. According to this reading, Jesus’ words are not taken as an abstract statement about bad things happening to good people. His pronouncement doesn’t equate Pilate’s murder of innocents with the accidental collapse of a building. Instead the two incidents are seen as mirror images of each other. Together they warn about the cycle of violence Jesus sees as destroying his people. This approach contextualizes Jesus’ words and takes seriously the political intent of the news item shared with Jesus at the very outset. Luke tells us,

“Some people told Jesus about the Galileans

whose blood Pilate had mingled with the blood of their sacrifices.”

No doubt, this was not news to Jesus. Everyone in Galilee must have been talking about it. Some Galileans – people from Jesus’ own province – had been slaughtered by Roman soldiers while offering sacrifice. The opening words of today’s gospel were not meant to communicate news but to complain about the Roman occupiers. Those introducing the topic were looking for sympathy and agreement. Jesus does not disappoint.

Pilate, of course, would have claimed that his victims were insurgents against the Roman occupation; they were “guilty” as terrorists, he would have said. That was his official line. Jesus says, “Don’t believe it” – as if his audience were tempted to believe Roman lies. “Do you think they were guilty?” Jesus asks. “By no means,” he answers.

Here Jesus is agreeing with his Galilean compatriots. If the ones Pilate killed were terrorists, he says, so are all Galileans; we’re all guilty in Pilate’s eyes. None of us wants the Romans here, Jesus implies. After all, it wasn’t the Galileans who threw the first stone; it was Pilate and the Roman soldiers who did so by invading Israel’s sovereign territory.

But then Jesus suddenly takes another tack. He connects Pilate’s butchery with another headline of his day – an act of counter-violence taken by the “Zealot” forces Pilate was attempting to punish. (Zealots were the revolutionary force committed to ousting the Roman occupiers from Palestine.) Pilate’s action, Jesus suggests, started the cycle of violence that evoked a disaster at Siloam at a spot near the Fountain of Ezekias. Siloam was the location of a small arsenal, where the Romans kept their swords, shields, battering rams and other weapons.

According to Maria and Ignacio Lopez-Vigil, a group of Zealot insurgents had tried to dig a tunnel up to the tower with hopes of seizing the weapons and turning them against the Romans. But the tower’s foundation was already in a state of decay, and the tunnel caused the entire construction to suddenly collapse. The falling tower claimed the lives of several Galilean families who had built their houses near the arsenal.

Jesus point: Pilate is certainly a bloodthirsty man. None of us want him or his armies on our soil. However, those who return his violence with their own are bloodthirsty too. And if we don’t reform our ways we’ll all drown in a bloody deluge. Or as Jesus put it, “I tell you, if you do not repent, you will all perish as they did!”

And time is running short, he adds with his parable about a fig tree. The bloody deluge has been building for at least three years. We have maybe another twelve months before the chickens of the deadly cycle of violence come home to roost. Without repentance, without replacing violent resistance to Roman butchery with non-violent tactics, we’ll all be cut down like a barren fig tree. (Later on, remember, Jesus himself demonstrates the kind of non-violent direct action he had in mind, with his “cleansing” of Jerusalem’s temple.)

Jesus’ prediction of bloodbath, of course, eventually comes true, but not as soon as he thought. The Romans would defeat the Zealot uprising in the year 70, and definitively squash all Jewish rebellion in 132. Jesus was right however about the extent of the slaughter. It was horrific resulting in the deaths of more than a million Jews. Such disaster is inevitable, Jesus teaches for all who “live by the sword.”

What does all of this say to us today? The message is quite relevant. It says first of all that we must be careful about domesticating Jesus and the gospel. The standard interpretation of this passage has the effect of making us comfortable with empire as somehow the instrument of God. It is not. Instead, empire represents the systematized oppression of the poor and defenseless by the rich and powerful. That was true of Rome; it’s true of U.S. empire today. We’re still killing insurgents in their churches and mosques.

Secondly, this passage calls us to non-violence and warns us about where the cycle of violence will inevitably lead. Sandy Hook provides a window into the world created by the worship of guns. Another window is provided by Afghanistan and Iraq, Vietnam, Hiroshima, the Cold War, and the general impoverishment of our country and world brought on by so-called “defense” spending. All of it has us drowning in a deluge of blood. And it promises to get worse and eventually destroy us all. How much time do we have before our chickens come home to roost – three years, one year. . .?

Christians represent about 30% of the world’s inhabitants. There are more than 2 billion of us. Imagine the world we’d create if we insisted on following the call to non-violence represented by Jesus’ words in this morning’s gospel!

![images16[1]](https://mikerivageseul.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/images161.jpg?w=300&h=209)

![Empires[1]](https://mikerivageseul.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/empires1.jpg?w=300&h=200)

![thevaginamonologues[1]](https://mikerivageseul.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/thevaginamonologues1.png?w=300&h=156)