Readings for the Second Sunday of Lent: Genesis 12: 1-4a; Psalm 33: 4-5, 18-19, 20,22; 2 Timothy 1: 8b-10; Matthew 17: 1-9

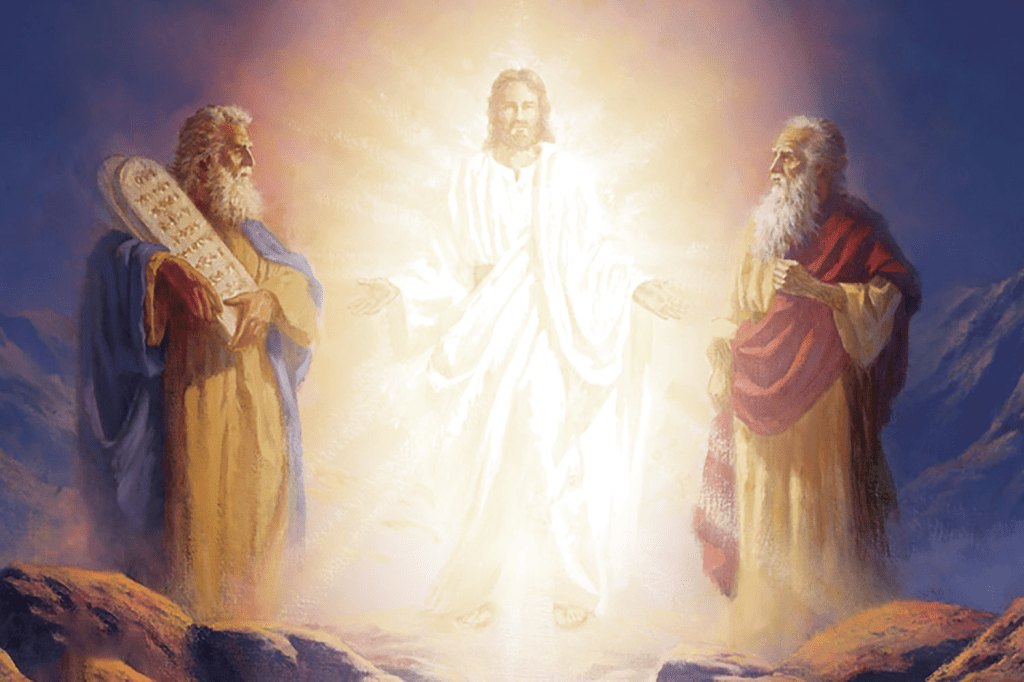

The Gospel reading for this Second Sunday of Lent is about the “transfiguration” of Jesus.

It’s about how the primitive Christian community’s understanding of Jesus and his significance changed following their experience of what they came to call his “resurrection.”

After that experience, whatever it was, they came to see him clearly as the New Moses and the New Elijah. As such he would introduce a New Order that would embody liberation of society’s most marginalized (Moses) and outspoken confrontation against the given imperial order (Elijah).

Jesus himself called that New Order the Kingdom of God.

It is what the world would look like if God were king instead of Caesar.

That vision should take on new meaning for Americans in the aftermath of Donald Trump’s disgraceful State of the Union Message last Tuesday. It should even embolden the profane response STFU.

Trump’s Un-transfigured World

If you watched the speech, you know what I mean.

It seemed like the dying gasp of the ruling Septuagenarian and Octogenarian classes.

It was a flailing, lie-filled proclamation of a Golden Age that never existed and that never will be if we follow the path the failed braggart president celebrated.

It was the opposite of God’s Kingdom – a world with room for everyone.

I mean, Trump’s SOTU celebrated division, wealth and power, and a militarism while targeting the poorest people on our planet. He had the staggering nerve to tone-deafly call them what the Epstein Files are revealing the political class itself to be: lawless rapists, pedophiles, robbers, drug dealers, gang members and murderers. And Trump’s crowd are blackmailers besides.

Making those allegations, the president revealed his own nakedness and that of his mindless Maga colleagues who mindlessly jumped to their feet to applaud the beauty of the Emperor’s non-existent robes.

Yes, the Files, the coverups, the sweetheart deals for Epstein and Maxwell, the redactions, the months-long failures to disclose, and the reduction of Pam Bondi’s Department of Justice to the President’s private law firm are revealing everything.

The Emperor indeed has no clothes. He’s shamelessly parading around stark naked and tiny.

And reminiscent of the Hans Christian Anderson story, it’s the little children he’s imprisoning (with their bunny ears and Spiderman backpacks) who proclaim the emperor’s embarrassing nudity.

No clothes! Naked! Tiny. Or as Joseph N. Welch put it to Senator Joseph McCarthy “Have you no sense of decency, sir, at long last?”,

Jesus’ Transfigured World

The tale of Jesus’ Transfiguration tells an opposite story.

It’s the story of a poor construction worker – a former immigrant, a prophetic teacher of unconventional wisdom, the death row inmate whom empire jailed, tortured and submitted to imperial capital punishment – whose life and teaching revealed a New Order that was shining and pure because it had room for everyone.

And in today’s reading, it’s his transformed clothes and the spiritual company he keeps that tell the story.

Matthew puts it this way: “His face shone like the sun and his clothes became white as light. And behold, Moses and Elijah appeared to them, conversing with him.”

That is, the one whose imperialized class status would eventually reduce him to nakedness on Mt. Calvary is perceived by his first followers as magnificently clothed.

Even more, Matthew’s account of Jesus’ Transfiguration has him conversing with Moses and Elijah.

Moses, of course, is the great liberator of the enslaved and poor.

Elijah was the courageous prophet who not only spoke truth to power but resisted false gods who take the side of the rich and powerful rather than God’s truly chosen ones, the poor and oppressed.

Don’t Let the Democrats off the Hook

But none of this should let the Democrats off the hook just because some of them refused to attend the STFU SOTU affair. Don’t let them get away with just not being Trump.

It’s time for us to echo Zohran Mamdani, the most popular politician in the country.

In my novella, Against All Odds: How Zohran Mamdani Became President and Changed America Forever, I imagine a moment like this. Not because of special foresight, but because systems built on secrecy, oligarchy, militarism, and spectacle inevitably crack. In that story, hidden ledgers surface. Blackmail networks become visible. The machinery of power is exposed. The old guard responds the only way it knows how — with louder threats, more force, and louder applause.

Sound familiar?

But exposure alone is not liberation.

Which brings us back to the mountain of Transfiguration.

That scene depicted there is not mystical escapism. It is political theology. It declares that the authority of empire is provisional — that the true sovereignty belongs to the God who sides with slaves, captives, resident aliens, and the poor.

Luke makes the program explicit: “He has anointed me to preach good news to the poor… to proclaim liberty to captives… to set at liberty those who are oppressed.”

That’s a rival social order.

And if the imperial system is unraveling before our eyes — if its nakedness is becoming visible — then what must follow is not nostalgia or revenge, but reconstruction.

In Against All Odds, the answer to systemic collapse is not personality cult or partisan fury, but the institution of a Republic of Care. It is clarity. It is the articulation of a simple, material program centered on ordinary people’s lives. Among others, the items in such a program would include:

- Affordability

- Universal health care

- Full employment

- Higher wages

- Free education through college

- Environmental protection

- Expanded voting rights

- An end to oligarchic distortions like the Electoral College

- Strict term limits in every branch of government

- Drastic reductions in military spending.

- No endless wars

- Immigration reform rooted in dignity

- The dismantling of structures whose primary function is coercion at home and abroad.

In liberationist terms, none of that is utopian dreaming. Mamdani’s election proved that. The reforms just listed are what happen when the needs of the poor become the criteria of policy.

Conclusion

Trump’s embarrassing speech was the voice of Caesar defending a crumbling temple.

The Transfiguration is the unveiling of another possibility altogether.

Empires grow louder when they weaken. They shout about enemies. They celebrate force. They promise greatness. That is what dying systems do.

But the biblical tradition suggests something else: when Pharaoh hardens his heart, liberation accelerates. When Ahab clings to power, Elijah’s voice sharpens. When Rome crucifies, resurrection faith spreads.

Lent invites us to see clearly — to recognize naked empire and to imagine, without apology, a transfigured order grounded in justice for the poor.

Our petite impotent emperor is exposed.

The question now is whether we have the courage to climb the mountain with Peter, James and John to see what comes next.