Readings for 4th Sunday of Lent: Jos. 5:9A, 10-12; Ps. 34:2-7; 2 Cor. 5: 17-21; Lk. 15: 1-3, 11-32 http://www.usccb.org/bible/readings/031013-fourth-sunday-of-lent.cfm

There’s a lot of anger in our culture these days, isn’t there? And a lot of anger among Christians. . . . That was apparent in the last elections – and really in the politics of the last 35 years or so. Over that period, Catholic and Evangelical fundamentalists (especially men) have identified more and more closely with conservative politics. That’s because conservative politicians have presented themselves as upholding what they take to be Christian values.

In the name of those values, they and their constituents find themselves resentful of the social advancement of African Americans, women, gays, welfare recipients, and undocumented immigrants. Such groups are seen as threatening Christian values with their alleged disregard of white middle class values around families, sexuality, work, and legality.

This morning’s gospel “Parable of the Prodigal Son” addresses resentment of that kind. It is one of the most beautiful and well-known stories in World Literature. However, standard readings of the parable domesticate it. They turn the parable into an allegory and in so doing rob it of the cutting edge which makes it relevant to our age of Angry White Christians. Please think about that with me.

Standard readings of “The Prodigal Son” make it a thinly veiled allegory about God and us. God is the father in the story, non-judgmental, full of compassion, willing to overlook faults and sins. Meanwhile, each of us is the wayward son who temporarily wanders away from home only to return after realizing the emptiness of life without God. The older brother represents the few who have never wandered, but who are judgmental towards those who have.

Such reading never fails to touch our hearts and fill us with hope, since the story presents such a loving image of God so different from the threatening Judge of traditional Christian preaching. And besides, since most of us identify with the prodigal rather than with the older brother, we’re drawn to the image of a God who seems more loving towards the sinner than towards the saint.

Though beautiful and inspiring, such allegorical reading distorts Jesus’ message, because it makes us comfortable rather than shaking us up. At least that’s what modern scripture scholarship tells us. Those studies remind us that Jesus’ stories were parables not allegories. Allegories, of course, are general tales in which each character stands for something else.

Parables on the other hand are very particular rather than being general stories about the human condition. Unlike allegories, they’re not about human beings in general – everywoman and everyman. Instead, parables are addressed to particular people – to make them uncomfortable with their preconceptions and cause them to think more deeply about the central focus of Jesus’ teaching, the Kingdom of God. In the gospels, Jesus’ parables are usually aimed at his opponents who ask him questions with an eye to trapping or discrediting him. Jesus’ parables turn the tables on his opponents and call them to repentance.

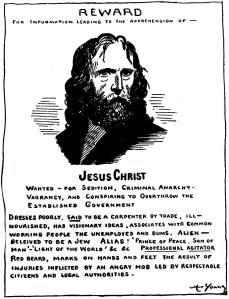

That’s the case with the “Parable of the Prodigal Son.” It contrasts two very particular historical groups absolutely central to the teaching career of Jesus of Nazareth. On the one hand, there is Jesus’ inner circle, “tax collectors and sinners.” These including sex workers, lepers, beggars, poor peasants, fishermen, shepherds, day-laborers, insurgents, and non-Jews, all of whom were especially receptive to Jesus’ teaching. On the other there are the Pharisees and Scribes. They along with the rabbis and temple priesthood were responsible for safeguarding the purity of the Jewish religion. They were Jesus’ antagonists.

Today’s gospel tells us that the sinners were “coming near to Jesus and listening to him.” For their part the Pharisees and Scribes stood afar and were observing Jesus’ interaction with the unwashed and shaking their heads in disapproval. They were “grumbling,” the gospel says, and saying, “This fellow welcomes sinners and eats with them.” That’s a key point in the reading – Jesus was eating with the hungry, poor, and unclean.

The gospel goes on, “So he told them this parable” – the parable of the prodigal son. In other words, the parable was addressed to the Pharisees and Scribes. And the story not about God and humans in general. It’s simply about a father and two sons and the way things work in the Kingdom of God, which (to repeat) was consistently the focus of Jesus’ preaching.

According to Jesus, that New Order will be a Great Party to which everyone is invited. The party will go on and on. There will be laughter, singing and dancing and the wine will never run out. The “fatted calf” will be slaughtered and there will be an overabundance of food. What fun!

Jesus was anticipating that order by practicing table fellowship with sinners and outcasts. At the kingdom’s banquet, the sinners gathered around Jesus in this morning’s gospel will be the first to accept the invitation. And though the Scribes and Pharisees are invited as well, they freely choose to exclude themselves. Like the older brother, they are “angry and refuse to go in.”

What I’m saying is that the lesson of today’s gospel (read as a parable rather than an allegory) is: Join the Party! Anticipate the New Order of the Kingdom in the here and now. Follow Jesus’ example, sit down with the unwashed, poor and despised. After all, the kingdom of God belongs to them – and to anyone (even the priests, scribes, rabbis, Pharisees, and any of us) who can overcome our reluctance to descend to Jesus’ level and to that of the kind of people he counted as his special friends.

What can that possible mean for us today? First of all it means don’t allegorize Jesus’ parables. It’s easy to understand how parables were turned into allegories as time passed. After all, Christians found themselves distanced further and further from the historical circumstances of Jesus in Galilee. They were looking for meaning and forgot who the scribes and Pharisees were. They forgot how those religious leaders despised the Great Unwashed. As well, with growing emphasis on heaven, Christians gradually lost capacity to recall the here and now nature of God’s Kingdom as envisioned by Jesus. They eventually came to identify it completely with the afterlife.

Additionally, there is no denying the truth to be found in allegorizing a parable like the Prodigal Son. Even according to the historical Jesus, God is good, forgiving, compassionate and non-judgmental. We are wayward people indeed. And like a loving father, God does receive us back no matter how far afield we may have gone. Nonetheless such allegorizing distorts the message of the historical Jesus which, as always, centralizes the Kingdom of God, and not the general human condition.

However, if we keep Jesus’ original meaning in mind, we’ll more likely see “the Prodigal Son” as a call to change our attitudes towards the second and third class citizens of our culture. That’s a hard message for most middle-to-upper class white people to hear. Like the culture of the professionally religious of Jesus’ day, our own despises those with whom Jesus ate and drank. In fact, it teaches us to dislike people like Jesus himself. Our culture sees those in Jesus’ class as lazy, dishonest, and undeserving.

So rather than making us feel more comfortable, today’s gospel should have the same effect Jesus’ parables in general were intended to have. It should make us squirm just as Jesus’ original words must have embarrassed the scribes and Pharisees.

But Jesus’ parable shouldn’t just embarrass us. His words should be hopeful too. Like the father in the parable, he’s telling us, his self-righteous sons and daughters, “We’re having a party. Why don’t you join us? Come in and share what you have, adopt God’s political program which creates a world with room for everyone – even the undeserving.”

In other words, it’s not God who excludes us from the Kingdom’s feast. It’s our own prejudice and choice.

![images16[1]](https://mikerivageseul.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/images161.jpg?w=300&h=209)

![Empires[1]](https://mikerivageseul.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/empires1.jpg?w=300&h=200)

![thevaginamonologues[1]](https://mikerivageseul.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/thevaginamonologues1.png?w=300&h=156)