Readings for 1st Sunday after Easter: Acts 5:12-16; Ps. 118: 2-4, 13-15, 22-24; Rev. 1: 9-11A, 12-13, 17-19; Jn. 20: 19-31. http://www.usccb.org/bible/readings/040713.cfm

The picture painted in today’s gospel story should be familiar to all of us. I say that not only because we have heard it again and again, but because it’s our story. It’s about a man in denial, the original doubting Thomas. Thomas’ nickname was “the twin.”

Whatever that meant originally, Thomas is undoubtedly our fraternal double in that he depicts our condition as would-be followers of Yeshua. Like Thomas we live in practical denial concerning the reality of Yeshua’s resurrection – about the possibility of a radically transformed life. Recall our twin’s story. Pray that it can be ours as well.

The disciples are there in the Upper Room where they had so recently broken bread with Yeshua the night before he died. And they are all afraid. John says they are afraid of “the Jews.” However it seems they fear death more than anything else. They dread it because they are convinced that death spells the end of everything they hold dear – their ego-selves, families, friends, culture, and their small pleasures. Besides that, they are afraid of the pain that will accompany arrest – the isolation cells, the beatings, torture, the unending pain, and the final blow that will bring it all to a close. Surely they were questioning their stupidity in following that failed radical from Galilee.

So they lock the doors, huddle together and turn in on themselves.

Nevertheless, the very fears of the disciples and recent experience make them rehearse the events of their past few days. They recall the details: how Yeshua so bravely faced up to death and refused to divulge their names even after undergoing “the third degree” – beatings followed by the dreaded thorn crown, and finally by crucifixion. All the while, he remained silent refusing to name the names his Roman interrogators were looking for. He died protecting his friends. Yeshua was brave and loyal.

His students are overwhelmingly grateful for such a Teacher. . . .

Then suddenly, the tortured one materializes there in their midst. Locks and fears were powerless to keep him out. They all see him. They speak with him. He addresses their fears directly. “Peace be with you,” he repeats three times. Yeshua eats with them just as he had the previous week. Suddenly his friends realize that death was not the end for the Teacher. He makes them understand that it is not the end for them either – nor for anyone else who risks life and limb for the kingdom of God. No doubt everyone present is overwhelmed with relief and intense joy.

“Too bad Thomas is missing this,” they must have said to one another.

Later on, Thomas arrives – our fraternal double in unfaith. His absence remains unexplained. Something had evidently called him away when the others evoked Jesus’ presence by their prayer, recollections, and sharing of bread and wine. Like us he hasn’t met the risen Lord.

“Jesus is alive,” they tell the Twin. “He’s alive in the realm of God. He took us all with him to that space for just a moment, and it was wonderful. Too bad you missed it, Thomas. None of the rules of this world apply where Yeshua took us. It was just like it was before he died. Don’t you remember? Yeshua brought us to a realm full of life and joy. Fear no longer seems as reasonable as it once did. He was here with us!”

However, Thomas remains unmoved. Like so many of us, he’s is a literalist, a downer. He’s an empiricist looking for the certainty of physical proof. Thomas is also a fatalist; he evidently believes that what you see is what you get. And for him there has been no indication that life can be any different from what his senses have always told him. Life is tragic. Death is stronger than life; it ends everything. And that means that Yeshua is gone forever. Who could be so naïve as to deny that?

Our twin in unfaith protests, “In the absence of physical proof to the contrary, I simply cannot bring myself to share your faith that another life is possible. And make no mistake: Yeshua’s enemies haven’t yet completed their bloody work. They’re after us too.”

Can’t you see Thomas glancing nervously behind him? “Are you sure those doors are locked?”

Then lightning strikes again. Yeshua suddenly materializes a second time in the same place. Locks and bolts, fear and terror – death itself – again prove powerless before him.

Yeshua is smiling. “Thomas, I missed you,” he says. “Look at my wounds. It’s me!”

Thomas’ face is bright red. Everyone’s looking at him. “My God, it is you,” he blurts out. “I’m so sorry I doubted.”

“Don’t worry about it,” Yeshua assures. “You’re only human, and I know what that’s like, believe me. I too knew overwhelming doubt. Faith is hard. On death row, my senses told me that my Abba had abandoned me too. I almost gave up hope. It’s like I’m your twin.

“But then I decided to surrender. And I’m happy I did. My heart goes out to you, Thomas. My heart goes out to all doubters. I’ve been there.

“However, it’s those who can commit themselves to God’s promised future in the absence of physical proof that truly amaze and delight me. Imagine trusting life’s goodness and an unseen future with room for everyone when all the evidence tells you you’re wrong! Imagine trusting my word that much, when I almost caved in myself? That’s what I really admire!

“My prayer for you, Thomas, and for everyone else is that you’ll someday experience the joy that kind of faith brings.

Working for God’s Kingdom – for fullness of life for everyone – even in the face of contrary evidence – that’s what faith is all about. May it be yours.”

May it be ours!

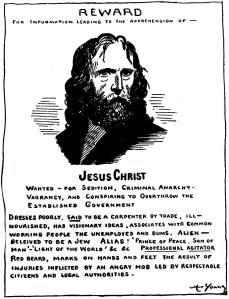

![images16[1]](https://mikerivageseul.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/images161.jpg?w=300&h=209)