Readings for the Third Sunday of lent: Exodus 17:1–7, Romans 5:1–2, 5–8, John 4:5–42.

The readings for this Third Sunday of Lent deal with the very human question of thirst. They raise the question, what are we thirsting for — ultimately?

Our politicians give us a glib answer. They tell us that our thirst is for security — from the threatening humans that surround us. The nation is dying we are told. We have lost our greatness. We are being overrun. Scarcity is closing in.

“Make America Great Again” is not just a slogan; it is an appeal to a deep anxiety — the fear that there is not enough: not enough jobs, not enough cultural cohesion, not enough safety, not enough control.

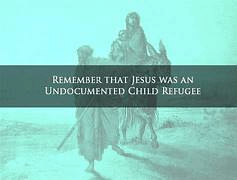

And so we are offered a diagnosis: the crisis is immigration. The problem is those people (who happen to be the poorest in the world!). The solution is walls, expulsions, exclusion. We are invited to believe that national greatness depends on tightening the circle.

But step back for a moment. The United States has 4 percent of the world’s population and consumes roughly a quarter of its resources. The “crisis” is narrated as though the most powerful nation in human history were a fragile victim of desperate families crossing deserts.

That story itself deserves scrutiny. It feels eerily similar to another story we heard today.

Thirst in the Desert

In Exodus 17, the people have escaped Egypt — escaped forced labor, escaped imperial extraction, escaped brick quotas. But once in the wilderness, they panic. There is no water. And fear rewrites memory. “Why did you bring us out of Egypt?” they ask. “Were there not enough graves there?”

Notice what is happening. A people freed from empire begin to long for the security of empire. Scarcity produces nostalgia. Anxiety produces accusation. Moses becomes the problem. Freedom itself becomes suspect.

And they ask the piercing question: “Is the Lord in our midst or not?”

That question echoes beneath our own political rhetoric. Is God present in pluralism, in equity, in inclusion? Is God present in demographic change? Is God present in movements of displaced people seeking survival? Or is God only present in the imagined stability of a past we have sanctified?

At Massah and Meribah, the people’s fear does not disqualify them. Yahweh brings water from rock. Not from Pharaoh’s storehouses. Not from a border wall. From a rock in the desert. The provision comes not through renewed control, but through trust in a God who sides with vulnerable people.

The biblical tradition has always insisted that this is the decisive revelation: God is known in history through concrete acts of sustenance for those escaping bondage. Not through slogans of greatness, but through water in the wilderness.

The Woman at the Well

Then we move to John’s Gospel, and the political charge intensifies.

Jesus is in Samaria — enemy territory. Centuries of ethnic hatred stand between Jews and Samaritans. Purity codes, historical grievances, competing temples. If ever there were a border crisis, this was it. And yet Jesus does not reinforce the boundary. He crosses it.

He asks a Samaritan woman for a drink.

It is astonishing. The one who will speak of “living water” begins by placing himself in need before someone religiously and socially marginalized. He does not begin with a lecture about law and order. He begins with vulnerability.

And this woman — doubly stigmatized as Samaritan and as female — becomes the first missionary in John’s Gospel. She leaves her jar and runs to her town: “Come and see.”

Our Real Thirst

What if the real thirst in our society is not for greatness, but for encounter? What if the deeper crisis is not immigration, but isolation? What if we have mistaken demographic change for existential threat because we have forgotten how to sit at wells with strangers?

“Living water,” Jesus says, becomes a spring within — not hoarded, not policed, not weaponized. It flows outward.

The irony is painful. The people who once wandered as refugees in the desert now fear refugees at their gates. The descendants of immigrants fear immigration. The community that drinks from a rock fears sharing water.

And beneath it all is that ancient question: “Is the Lord in our midst or not?”

If God is only with the secure, then fear makes sense. But if God is the One who hears slaves, who provides water for rebels, who speaks across enemy lines, then perhaps the presence of the stranger is not a threat but a test.

Paul, in Romans, says that “the love of God has been poured into our hearts.” Poured. Abundance language. Not scarcity language. Not zero-sum logic. Poured out while we were still estranged, still flawed, still confused.

Conclusion

Lent invites us to examine our thirst honestly. Are we thirsty for justice — or for dominance? For community — or for control? For security — or for solidarity?

Greatness, in the biblical sense, is never about territorial assertion. It is about fidelity to the God who brings water from rock and who offers living water at a contested well.

The wilderness is frightening. Demographic change is unsettling. Empires promise certainty. But the Gospel suggests that life springs up not from walls, but from wells.

The bush still burns. The rock still flows. The well is still there.

The only question is whether we will drink — and whether we will let others drink too.