Peggy and I were shocked Sunday night when we received the stunning news that Fr. John Rausch, a very dear friend of ours, had died suddenly earlier in the day. John was a Glenmary priest whom we had known for years. He was 75 years old.

At one point, John lived in a log cabin below our property in Berea, Kentucky. So, we often found ourselves having supper with him there or up at our place. John was a gourmet cook. And part of having meals with him always involved watching his kitchen wizardry while imbibing Manhattans and catching up on news – personal, local, national, and international. Everything was always interspersed with jokes and laughter.

That’s the kind of man John was. He was a citizen of the world, an economist, environmentalist, prolific author, raconteur, and social justice warrior. But above all, John was a great priest and an even better human being full of joy, love, hope, fun, and optimism.

Yes, it was as a priest that John excelled. Everyone who knew him, especially in the progressive wing of the Catholic Church, would agree to that. Ordained in 1972 [just seven years after the closure Vatican II (1962-’65)] John never wavered in his embrace of the Church’s change of direction represented by the Council’s reforms.

According to the spirit of Vatican II, the Church was to open its windows to the world, to adopt a servant’s position, and to recognize Jesus’ preferential option for the poor. John loved that. He was especially fervent in endorsing Pope Francis’ extension of the option for the poor to include defense of the natural environment as explained in the pope’s eco-encyclical, Laudato Si’. (To get a sense of John’s concept of priesthood and care for the earth, watch this al-Jazeera interview that appeared on cable TV five years ago.)

His progressive theology delighted John’s audiences who accepted the fact that Vatican II remains the official teaching of the Roman Catholic Church. So, as two successive reactionary popes (John Paul II and Benedict XVI) subtly attempted to reverse conciliar reforms, and as the restorationist priests and bishops they cultivated tried mightily to turn back the clock, John’s insistence on the new orthodoxy was entirely refreshing.

I remember greatly admiring the shape of John’s homilies that (in the spirit of Pope Francis’ Evangelii Gaudium) were always well-prepared and followed the same pattern:

- He’d begin with two or three seemingly unrelated vignettes involving ordinary people with names and usually living in impoverished Appalachian contexts.

- For the moment, he’d leave those word-pictures hanging in the air. (We were left wondering: “What does all that have to do with today’s readings?”)

- Then, on their own terms, John would explain the day’s liturgical readings inevitably related to the vignettes, since Jesus always addressed his teachings to the poor like those in John’s little stories.

- Finally, John would relieve his audience’s anxiety about connections by perfectly bringing the vignettes and the readings together – always ending with a pointed challenge to everyone present.

The result was invariably riveting, thought-provoking and inspiring. It was always a special day whenever Fr. John Rausch celebrated Mass in our church in Berea, Kentucky.

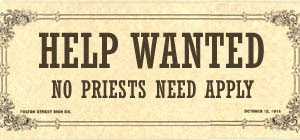

Nevertheless, John’s social justice orientation often did not resonate with those Catholics out-of-step with official church teaching. These often included the already mentioned restorationist priests and bishops who harkened back to the good old days before the 1960s. Restorationist parishioners sometimes reported Fr. Rausch to church authorities as “too political.”

But Fr. Rausch’s defense was impregnable. He was always able to appeal to what he called “the best-kept secret of the Catholic Church.” That was the way he described the radical social encyclicals of popes from Leo XIII’s Rerum Novarum (1891) through Pius XII’s Quadragesima Anno (1931), Vatican II’s Gaudium et Spes (1965), and Pope Francis’ Laudato Si’ (2015).

John was fond of pointing out that all of those documents plus a host of others were consistently critical of capitalism. They favored the demands of working classes, including living wages, the right to form labor unions, and to go out on strike. Other documents were critical of arms races, nuclear weapons, and modern warfare in general. “You can’t get more political than that!” John would say with his broad smile.

All that perseverance on John’s part finally paid off when his local very conservative bishop was at length replaced by a Franciscan friar whom I’ve described elsewhere as “channeling Pope Francis.” I’m referring to John Stowe whose brown-robe heritage had evidently shielded him from the counter-reforms of the two reactionary popes previously mentioned.

When Bishop Stowe assumed office, he evidently recognized John as a kindred spirit. He respected his knowledge of Appalachia and his desire to connect Church social teachings with that context. So, the new bishop asked John to take him on an introductory tour of the area. John was delighted to oblige. He gave Bishop Stowe the tour John himself had annually led for years. It included coal mines, the Red River Gorge, local businesses, co-ops, social service agencies, local churches, and much more. John became Bishop Stowe’s go-to man on issues involving those represented by the experience.

But none of that – not John’s firm grounding in church social teaching, not his success as a liturgist and homilist, not his acclaimed workshops on economics and social justice, not his long list of publications, nor his advisory position with Bishop Stowe – went to John’s head.

He never took himself that seriously. He was always quick with the self-deprecating joke or story.

In fact, he loved to tell the one about his short-lived movie career. (I’m not kidding.) It included what he described as his “bedroom scene” with actress Ashley Judd. It occurred in the film, “Big Stone Gap.” I don’t remember how, but in some way, the film’s director needed a priest for a scene where Ms. Judd was so deathly ill that they needed to summon a member of the clergy. John was somehow handy. So, he fulfilled the cameo role playing himself at the bedside of Ashley Judd. (See for yourself here. You’ll find John credited as playing himself.) Right now, I find myself grinning as I recall John’s telling the tale. It always got a big laugh.

Other recollections of John Rausch include the facts that:

- For a time, he directed the Catholic Committee on Appalachia.

- He also worked with Appalachian Ministries Educational Resource Center (AMERC) introducing seminarians to the Appalachian context and its unique culture.

- He published frequently in Catholic magazines and authored many editorials in the Lexington Herald-Leader. John’s regular syndicated columns reached more than a million people across the country.

- He had a strong hand in the authorship of the Appalachian bishops’ pastoral letter “At Home in the Web of Life.”

- He led annual pilgrimages to what he called “the holy land” of Appalachia as well as similar experiences exploring the culture and history of the Cherokee Nation.

- He was working on his autobiography when he died. (I was so looking forward to reading it!)

More Personally:

- He graciously read, advised, and encouraged me on my own book about Pope Francis’ Laudato Si’.

- I have fond memories of one Sunday afternoon when he invited me to a meeting in his living room with other local writers. We were to read a favorite selection from something each of us was working on.

- John often came to my social justice related classes at Berea College to speak to students about Appalachia its problems, heroines and heroes. (Of course, to my mind, John ranked prominently among them.)

- He gave a memorable presentation along those lines in the last class I taught in 2014. John was a splendid engaging teacher.

Peggy and I are still reeling from the unexpected news of this wonderful human being’s death. For the last day we’ve been sharing memories of John that are full of admiration, reverence, sadness – and smiles. It’s all a reminder of our own mortality and of the blessing of a quick, even sudden demise.

Along those lines, one strange thought that, for some reason, keeps recurring to me is that John’s passing (along with that of another dear friend last month) somehow gives me (and John’s other friends) permission to die.

I don’t know what to make of that. It might simply be that the two men in question (like Jesus himself) have gone before us and shown the way leading to a new fuller form of life. Somehow, that very fact makes the prospect of leaving easier. Don’t ask me to explain why or how.

Thank you, John.

![Ordination[1]](https://mikerivageseul.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/ordination1.jpg)