This is my 4th blog entry connected with a course I’ve been taking in New York City for the past 7 weeks. The course is called “The Frankfurt School and the Paradoxical Idea of Progress: Thinking beyond Critical Theory.” It’s taught by the great critical theory scholar, Stanley Aronowitz and has been a great joy for me. I love the subject; my classmates are very smart, and Stanley is . . . well, Stanley. He’s provocative, delightfully quirky, and extremely sharp even after the stroke that (at his age of 85) has confined him to a wheelchair. It’s a great privilege studying with him. As you can see from my previous blogs here, here, here, and here, the course readings from Theodore Adorno, Herbert Marcuse, and Walter Benjamin have been challenging. The ones analyzed below are equally so. This week, my responses are to Marcuse’s Eros and Civilization, and to a brief essay from Walter Benjamin called “Theses on the Philosophy of History.”

___________________________________________________________________

Herbert Marcuse, Walter Benjamin and the Teachings of the Hunchback Paul of Tarsus

What is the basis of critical thinking? Is it rationality? Is it logic? No, it’s theology.

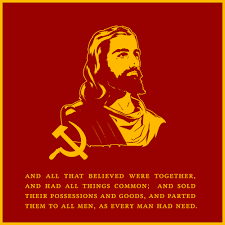

That, at least, is the implied argument of the critical theorists, Herbert Marcuse and Walter Benjamin. For them, the foundation of critical thought is what economist and liberation theologian, Franz Hinkelammert (the convener Costa Rica’s Critical Thinking Group) terms “the critique of mythic reason.” That is, the foundation of critical thought for Marcuse and Benjamin is myth involving interaction between human beings and the divine or ineffable transcendent. Marcuse’s preferred mythology is Greek. Benjamin suggests that his derives from the Judeo-Christian tradition in general and from St. Paul in particular.

The purpose of what follows is to summarize and offer some brief commentary on the relevant arguments of both Marcuse and Benjamin. To do so, this essay will first of all place Marcuse’s use of mythology within the context of his more general argument as outlined in his Eros and Civilization. Marcuse’s thought will then be compared with that of Walter Benjamin as expressed in his “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” with each Benjamin’s highly poetic 18 theses “translated” into more straight-forward prose. The essay will conclude by arguing that Benjamin’s theological approach is more effective than Marcuse’s in terms of critical theory. It will add, however, that Benjamin’s use of the Judeo-Christian tradition stops short of the depth achieved by Hinkelammert’s commentary informed by the theology of liberation – and in particular by Hinkelammert’s analysis of the writings of Paul of Tarsus whose thought he identifies as the root of what has come to be known as critical theory.

Eros and Civilization

Herbert Marcuse’s seminal Eros and Civilization attempts to elaborate the critical implications of Freud’s psychoanalytic theory (245). In doing so, it builds on the model of repression so brilliantly explained by Freud in his own Civilization and its Discontents. Marcuse connects Freud’s theory of the inevitable conflict between civilization and its laws on the one hand, and the fundamental human drive for complete happiness on the other.

With Freud, Marcuse identifies that drive with the Greek word Eros understood on his view, as much more expansive than mere sexual love (205). In doing so, Marcuse acknowledges the term’s mythological roots. Even more, Christian theologians might find theological overtones in his use of Eros which arguably makes the drive for complete happiness equivalent to “God” as described by the author of the Christian Testament’s First Letter of John which identifies God with love itself (I JN 4:7-21).

In the process of stating his argument, Marcuse critically reviews the stages of human development shared by all human beings from birth, through early family life, education, employment, marriage, later family life, and death.

Marcuse notes that throughout those stages, humans gradually internalize restrictions on the self-centered drives (especially sexual) common to all humans. Such restrictions are necessary for the ordering of human community that avoids Hobbes war of each against all. Nevertheless, Marcuse finds that the social control required for such order soon develops into “surplus repression” far beyond that required for rational order (35, 37, 87f, 131, 235).

In the light of that reality, Marcuse’s overriding question becomes how to identify and escape excessive control that ends up serving the interests of dominant few, while immiserating all others. The chief misery imposed by those classes is that of alienated labor which requires that humans spend most of their lives performing (and recovering from) mind-numbing and body-destroying activities that have little or no intrinsic value (45).

Again, in order to answer his question about exiting this situation, Marcuse traces the origins of surplus repression. It begins, of course, in the family with a child’s relationship to his parents, especially (in the west’s patriarchal culture) with one’s relationship to father. Following the pattern of Freud’s myth of the primal horde, male children begin their lives confronted with a father who unreasonably imposes surplus repression upon them. His excessive demands cause rebellion paralleling that described in the Primal Horde myth (15). However, in most cases, rather than actually murdering the father, rebellion usually takes the form of sexual deviation from patriarchal restrictions.

Deviation from sexual restrictions is especially important, because (in the words of Erich Fromm) “Sexuality offers one of the most elemental and strongest possibilities of gratification and happiness.” Moreover, “. . . the fulfillment of this one fundamental possibility of happiness” of necessity leads to “an increase in the claim for gratification and happiness in other spheres of the human existence” (243). In other words, the human sexual drive represents the spearhead of Eros, the fundamental life force. That basic drive, Marcuse argues, lurks at the heart of all rebellion against civilization’s super-repression.

Eros differs from sexuality in that it is far less focused on genitalia (205). Even more, it locates its contested terrain on the fields of myth, art, philosophy, liberating education, and play.

Play proves especially important for Marcuse, because (in contradiction to society’s demands for productivity – and its “performance principle” expressed in alienated labor) “play is unproductive and useless precisely because it cancels the repressive and exploitative traits of labor and leisure” (195). It manifests existence without anxiety or compulsion and thus incarnates human freedom (187).

As noted earlier, the repressed human drive towards such liberation finds expression in philosophy, art, folklore, fairy tales, phantasy, and myth. Marcuse finds the latter especially expressive in the cases of Orpheus, Dionysius, Prometheus, Narcissus, Pandora. Accordingly, he devotes two entire chapters (8 &9) to analysis of Greek mythology. Myths provide instances of phantasy’s expression that “speaks the language of the pleasure principle, of freedom from repression, of uninhibited desire and gratification” (142).

Nevertheless, phantasies based on Greek mythology, though preserving the truth of “The Great Refusal” (to be entirely controlled by alienated labor), remain according to Marcuse’s analysis, “entirely inconsequential” in terms of actual resolving the problem in question (160).

In other words, while Marcuse focuses on a divine Eros in a promising way, he throws up his hands regarding the question of how to talk about its liberating reality to those for whom the very Greek mythology he finds so meaningful lacks resonance. He similarly characterizes folklore, fairytale, literature and art as also insignificant in terms of yielding a reality principle that realistically provides liberation from the “surplus repression” of the one that prevails (160).

This leads to the question: if Greek mythology is so ineffective, then why spend two chapters on the subject? Why did not Marcuse instead explore the liberating dimensions of the mythology of the Judeo-Christian tradition with which so many in the West can indeed identify? It might even be said that for the 75% of “Americans” who identify as Christian, their religious tradition amounts to a kind of underlying popular philosophy that supplies meaning for their lives. Therefore, finding and describing connections between that tradition and liberation from surplus repression would hardly be “inconsequential.”

Clearly, Marcuse was aware of such possibilities. His friend and Frankfurt School colleague, Erich Fromm, had already identified them in his The Dogma of Christ also published (like Eros and Civilization) in 1955. Moreover, Marcuse himself references such possibilities in Eros and Civilization, although he doesn’t elaborate the allusion. There, he observes:

“The message of the Son was the message of liberation: the overthrow of the Law (which is domination) by Agape (which is Eros). That would fit in with the heretical image of Jesus as the Redeemer in the flesh, the Messiah who came to save man here on earth. Then the subsequent transubstantiation of the Messiah, the deification of the Son beside the Father would be a betrayal of his message by his own disciples – the denial of the liberation in the flesh, the revenge on the redeemer. Christianity would then have surrendered the gospel of Agape-Eros again to the Law . . .” (69-73)

Here Marcuse introduces a crucial distinction between the actual teachings of Jesus of Nazareth on the one hand and his “transubstantiation” from a human being into the very equal of God. Beforehand, Marcuse says, Jesus was actually a heretic, an earthly Messiah intent on liberating actually existing human beings from oppressive legal systems. His followers, however gradually transformed his liberating Gospel of Agape-Eros into an instrument enforcing a super-repressive Law.

Having opened this promising door of critical analysis, Marcuse unexplainedly leaves it ajar without pursuing its promise.

Benjamin’s 18 Theses

In his final entry in Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, a collection of Walter Benjamin’s works reflecting his work as a critical theorist, Walter Benjamin ventures into the realm of Judeo-Christian theology that Marcuse so carefully avoids. Benjamin does so in the context of offering a series of eighteen theses on historical materialism and its philosophy of history. By the way, I take “historical materialism” to mean the philosophical conclusion holding that historical experience creates ideas rather than ideas creating historical experience.

Following this conclusion, Benjamin presents a highly contextualized approach to history wherein each of the latter’s moments is shaped by all previous ones as well as by prevailing ideologies and the historian’s own experience of life.

In other words, the writing of history is not simply a matter of recording events that unfolded in time understood as homogenous and empty of cultural influences and repercussions from what came before. Neither is it merely a matter of recording the past for the sake of preserving disconnected memories. Rather, historiography has the social purpose of shedding light on present dangers and crises for purposes of discovering exits from such existential threats.

Crucially for Benjamin (as already indicated), historical method is not only materialistic in the sense just referenced; it is also highly theological. As we shall see, Benjamin’s very first thesis in his list of 18 makes this point by suggesting Pauline theology as the guiding force of critical thought. Subsequently, virtually every thesis in the author’s list contains some reference to elements such as: theology itself (253), redemption, Messianic power, Judgment Day, the kingdom of God, spiritual things (254), good tidings, the Messiah, redeemer, Antichrist (255), theologians (256), angels, Paradise (257), monastic discipline, friars, meditation, Protestant ethics (258), savior (259), mysticism (261), Messianic time (263), the Torah, and prayer (264).

Moreover, like medieval religious practice, Benjamin’s theses are intended to turn the attention of readers away from the world and its affairs – but this time as described by traitorous politicians entrapped by a stubborn belief in the religion of progress (258). In fact, given Benjamin’s theological interests (4, 253) it is easy to interpret his theses on the philosophy of history as attempts to reinterpret theology in the service of historical materialism.

All of this may become evident in the following summaries of each our author’s 18 theses:

Thesis I: In an atmosphere of smoke and mirrors, and guided by theology, critical thought in the form of historical materialism promises inevitable victory over its opponent – viz. automated technology. And this, despite the latter’s deceptions that distort and reverse perception of reality into its mirror-opposite.

Thesis II: Historical materialists agree that Past (lost opportunities), Present (attempts to reverse those losses) and future (refusal to deal with the consequences of present action) exist in dynamic dialectical relationship captured by the words of history, redemption, and envy.

Thesis III: It is true that no event is insignificant in the long course of history. However, the significance of particular events can only be known at history’s conclusion.

Thesis IV: Despite apparent setbacks in workers’ struggles against ruling class domination, the long arc of history bends towards the victory of the poor and oppressed, because their subtle courage, humor, cunning and fortitude are more powerful than the gross tools of their oppressors.

Thesis V: Historical materialists (vs. mere chroniclers of past events) realize that recollection of past events is valuable only insofar as those events relate to and illuminate the present.

Thesis VI: The threats represented by ruling class attempts to reduce traditions about the past to tools supporting conformism must be resisted so that the past’s recollection might serve resistance and liberation instead.

Thesis VII: Historians who recount history without connecting it to present existential threats serve the interests of the world’s rulers (past and present) who steal the spirit and artifacts of those they’ve subdued. Historical materialists swim against that current.

Thesis VIII: History must reflect the “pedagogy of the oppressed,” which makes us aware of the changes necessary to overcome the perennial state of danger that has always characterized human existence and its struggle against oppression, which even its opponents treat as inevitable.

Thesis IX: As history’s messengers (angels), historical materialists perceive “progress” as responsible for an unending series of catastrophes. Ironically however, the devastating power of those very calamities prevents historical materialists from successfully alerting audiences to their own loss and lack of perception.

Thesis X: The accepted understanding of history (as a detached chronicling of the past) only serves traitorous politicians who have surrendered to fascism with its uncritical belief in progress, its manipulation of the masses, and its totalitarian structures.

Thesis XI: The conformity of the German working class is grounded in the conviction that “progress” includes and benefits its members. Alienated and enslaving factory work has been dignified by this belief. However, contrary to the convictions of “vulgar Marxism,” technology need not destroy, but could actually enhance and make nature more fruitful.

Thesis XII: It is angry recollection of the past rather than concern for the future and future generations that inspires resistance and rebellion in the working class which is the real repository of meaningful history.

Thesis XIII: Any valid critique of the Social-Democratic concept of progress (as anthropocentric, boundless, and irresistible) must be context-based rather than ignorant of historical context – as is the common Social-Democratic understanding of history.

Thesis XIV: Since only the present moment (the mystical nunc stans) is real, any consideration of the past has value only insofar as it sheds light on the present always characterized by ruling-class domination.

Thesis XV: Revolutionary holidays stop the ongoing continuum of history at decisive junctures – eternalizing the moment of liberation like the clocks simultaneously stopped by bullets on the first evening of fighting in the French Revolution, July 1789.

Thesis XVI: In contrast to historicists, historical materialists experience the present not as a transition to the future, but as an end in itself shaped by past events.

Thesis XVII: Unlike historicism, materialist historiography is not merely additive and does not treat time as homogenous, empty and inexorably in motion. The materialist approach is more contemplative, since it allows thinking (and therefore time) to stop so that history’s flow might be perceived as a unified whole. This pause and perception enables the historian (and his audience) to identify history’s underlying oppression and to uncover openings (past and present) for revolutionary change as the overriding project of one’s life.

Thesis XVIII: Humankind’s 50,000-year stature in a 14 million-year-old universe is nearly insignificant. As a result: (A) Alleging causal connections between historical events remains highly speculative (though any given present is both influenced by the past and contains intimations of a salvific future) and (B) the Jewish concept of time (as fundamental openness to a better future) is helpful here, since it is neither empty nor homogenous, nor magical.

Franz Hinkelammert’s Reading of Benjamin

Analyzing the story recounted in Benjamin’s first thesis on the philosophy of history, liberation theologian, Franz Hinkelammert specifically connects Benjamin with Paul of Tarsus and with critical theory. In doing so, Hinkelammert advances the theory of this brief review, viz. that theology constitutes the foundation of critical theory.

In fact, Hinkelammert considers Paul as the West’s first critical thinker. As such, Paul’s thinking, Hinkelammert argues, anticipates critical theory’s historical materialism, universalism, anarchism, and identification of the messianic function of the world’s poor and oppressed (Hinkelammert: La malidicion que pesa sobre la ley: Las raices del pensamiento critico en Pablo de Tarso. Editorial Arlekin. San Jose, Costa Rica, 2010. 16). More specifically, Hinkelammert recognizes the apostle as the hunchback pulling the strings of the puppet (historical materialism) in Benjamin’s cryptic parable (pictured above) recounted in the opening lines of “Theses on the Philosophy of History.”

Hinkelammert justifies doing so on the basis of the following observations:

• By his own admission, Benjamin’s basic orientation was decidedly towards the biblical past.

• He lamented that the biblical “wizened” founders of modern thought remained hidden and out-of-sight (Benjamin 253, Hinkelammert 23).

• In one of Benjamin’s surviving fragments, the latter’s closest friend, Gershom Scholem, celebrated Paul as the most notable example of a revolutionary Jewish mystic (Hinkelammert 14).

• Like the hunchback in Benjamin’s story, Paul suffered from some kind of physical deformity as described in II COR 12:7-9.

• Benjamin description of the parable’s puppet as wearing “Turkish attire” reminds us that its hidden alleged puppet-master, St. Paul, came specifically from Tarsus which is located in modern day Turkey (Hinkelammert 15).

• Other commentators like Jacob Taubes have found the presence of Paul’s thinking prominent not only in Benjamin, but in the most important currents of modern thought including that of Freud and Nietzsche. (The latter by the way, signaled support for this review’s thesis by villainizing Paul for the apostle’s anarchism, defense of the poor and oppressed, and prefiguration of Marx and of historical materialism) (16).

• Above all, Paul’s criticism of Law as the sin of the world, prepared the way for critical theory’s criticism of market law and of the state as the armed force imposing the will of the ruling class on the oppressed majority (17). For both Paul and critical theorists, complying with an oppressive law remains completely immoral (18).

Conclusion

Tellingly for this review’s thesis – that theology is the basis of critical theory – Hinkelammert points out that after Benjamin’s suicide in 1940, his fragment “Capitalism as Religion” came to light. The fragment drew a direct line from orthodox Christianity to capitalism whose system and ideology, Benjamin argues, replicates point-by-point (in secular terms) the elements of medieval Catholic orthodoxy.

However, according to Hinkelammert, Benjamin failed to note, much less exploit, the critical difference between such orthodoxy and the original message and praxis of the thoroughly Jewish prophet, Jesus of Nazareth. Had he done so, Hinkelammert observes, Benjamin would have strengthened his conclusion about the connections between Paul and historical materialism, since the teachings of St. Paul followed so closely those of the radical prophet and mystic Jesus of Nazareth.

In the end, it is Paul’s critique Law as well as the apostle’s anarchism and defense of the poor that prefigures the elaborations of Marx and Freud as understood by critical thinkers Benjamin and Marcuse. Only by embracing Paul’s influence, Benjamin correctly observes, can historical materialism claim its assured destiny as victor over the technological automaton intent on destroying us all.

Contemporary critical thinkers and activists would do well to heed Benjamin’s advice. They would do well to join liberation theologians in exploiting the popular power of a reinterpreted Judeo-Christian tradition that supports subversion, anarchism, and the hermeneutical privilege of the poor.