This is an “easy essay” (in the spirit of Peter Maurin’s contributions to “The Catholic Worker”). It is a follow-up to Monday’s posting about Dietrich Bonhoeffer and the Nazis’ reincarnation in today’s United States. It explains how Hitler actually prevailed in World War II (the Second inter-capitalist war). The “essay” references Marge Schott, the then-owner of the Cincinnati Reds, who in 1996 famously said that “Hitler was good in the beginning, but went too far.” The caption under the picture above reads in Spanish: “Hitler Won the War”

Following Germany’s defeat

in “the First Inter-Capitalist War,”

the system was in trouble in “das Vaterland.”

It also foundered world-wide

after the Crash of ‘29.

So Joseph Stalin

convoked a Congress of Victory

to celebrate the death of capitalism

and the End of History —

in 1934.

Both Hitler and F.D.R.

tried to revive the corpse.

They enacted similar measures:

government funds to stimulate private sector production,

astronomically increased defense spending,

nationalization of some enterprises,

while carefully keeping most in the hands of private individuals.

To prevent workers from embracing communism,

both enacted social programs otherwise distasteful to the Ruling Class,

but necessary to preserve their system:

legalized unions, minimum wage, shortened work days, safety regulation, social security . . .

Roosevelt called it a “New Deal;”

Hitler’s term was “National Socialism.”

Roosevelt used worker discontent

with their jobs and bosses

to get elected four times.

Meanwhile, Hitler successfully directed worker rage

away from the Krupps and Bayers

and towards the usual scapegoats:

Jews, communists, gays, blacks, foreigners and Gypsies.

He admired the American extermination of “Indians”

and used that model of starvation and internment

to guide his own program for eliminating undesirables

by hunger and concentrated slaughter.

Hitler strictly controlled national unions,

thus relieving the worries of the German elite.

In all of this,

he received the support of mainline churches.

Pius XII even praised der Führer as

“an indispensable bulwark against the Russians.”

Dietrich Bonhoeffer and the German “Confessing Church”

resisted Hitler’s program

of social Darwinism, patriotism and persecution of the undeserving.

Confessing faithful were critical of “religion”

which combined anti-Semitism, white supremacy, patriotism and xenophobia

with selected elements of Christianity.

They insisted on allegiance

to Jesus alone

who stood in judgment over soil, fatherland, flag and blood.

They even urged Christian patriots

to pray for their country’s defeat in war.

Bonhoeffer participated in a plot to assassinate Hitler

and explored the promise of

Christianity without “religion.”

Hitler initially enjoyed great popularity

with the powerful

outside of Germany,

in Europe and America.

He did!

Then as baseball magnate and used car saleswoman, Marge Schott, put it,

“He went too far.”

His crime, however, was not gassing Jews,

but trying to subordinate his betters in the club

of white, European, capitalist patriarchs.

He thus evoked their ire

and the “Second Inter-Capitalist War.”

Following the carnage,

the industrialists in other countries

embraced Hitlerism without Hitler.

They made sure that communists, socialists and other “partisans”

who bravely resisted German occupation

did not come to political power,

but that those who had cooperated with Nazis did.

Today, the entrepreneurial classes

still support Nazis, whenever necessary.

The “Hitlers” they championed have aliases

like D’Aubisson (El Salvador), Diem (Vietnam), Duvalier (Haiti), Franco (Spain),

Fujimori (Peru), Mobutu (Zaire), Montt (Guatemala), Noriega (Panama), Peron (Argentina),

Pinochet (Chile), Resa Palavi (Iran), Saddam Hussein (Iraq), Somoza (Nicaragua), Strossner

(Paraguay), Suharto (Indonesia). . . .

The list is endless.

The global elite deflect worker hostility

away from themselves

towards communists, blacks, gays, immigrants and Muslims,

towards poor women who stay at home

and middle class women who leave home to work.

Today, Christians embrace social Darwinism

while vehemently rejecting evolution.

Standing on a ground of being

underpinning the world’s most prominent culture

of religious fundamentalism,

they long for Hoover,

and coalesce

with the right.

In all of this

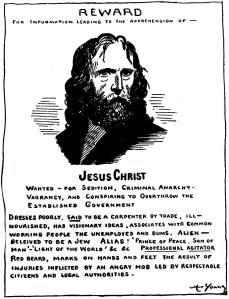

is forgotten the Jesus of the Christian Testament

who was born a homeless person

to an unwed,

teenage mother,

was an immigrant in Egypt for a while,

came from the working poor,

was accused of being a drunkard,

a friend of sex workers,

irreligious,

possessed by demons

and condemned by the state

a victim of torture

and of capital punishment.

Does this make anyone wonder about Marge Schott,

the difference between Hitler’s system

and our own,

and also about “religion”

and how to be free of it,

about false Christs . . . .

And who won that war anyway?

![Empires[1]](https://mikerivageseul.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/empires1.jpg?w=300&h=200)

![ash-wednesday-1[1]](https://mikerivageseul.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/ash-wednesday-11.jpg?w=270&h=300)

![th[7] (2)](https://mikerivageseul.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/th7-2.jpg?w=660)