Last night we had another meeting of our church’s Lenten series discussing controverted questions of faith. So far, we’ve discussed (1) miracles, (2) healing, (3) Jesus and the poor, (4) the tension between American and Christian identities, and (5) what happens after death. Next week, we’ll address the question of resurrection. It’s all been interesting and at times quite inspiring to interact with more than a dozen gifted and earnest fellow seekers in a very admirable faith community.

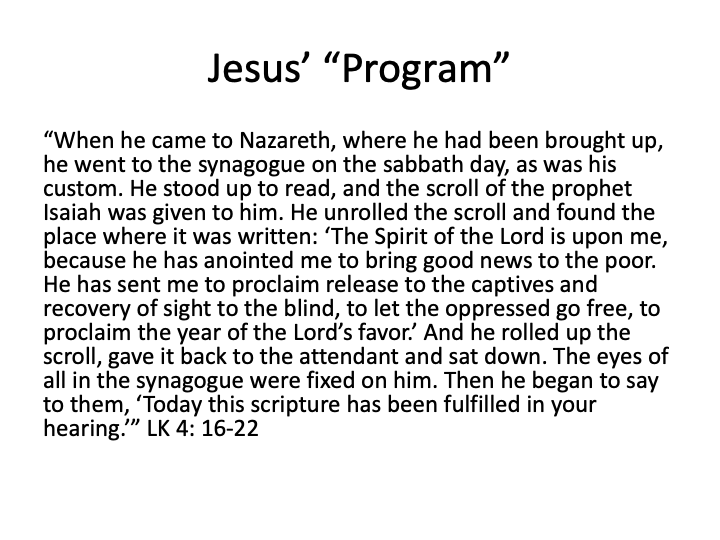

However (if you recall), a couple of weeks ago when I was asked to lead the session on Jesus and the Poor, I got “hooked” into defending (at inappropriate length) the centrality of the biblical “preferential option for the poor” as the heart of Christianity. The one who hooked me is a very friendly, intelligent, articulate, and sincere church member whose faith convictions are undeniably robust. I admire him greatly.

Nevertheless, during last evening’s meeting, it almost happened again. I mean, I was tempted to respond that same interlocutor rather than biting my tongue regarding a revisitation of our topic of two weeks ago about Jesus’ identity. (Remember, last night’s topic was to be what happens after death.)

Instead, my friend in the evening’s opening remark said something like the following: “We’re supposed to be Christians here discussing our faith. But the readings we’ve shared not only this week but two weeks ago, depart quite radically from central Christian beliefs. For instance, this evening’s reading is by Marcus Borg who sees Jesus is nothing more than a prophet. In this, he agrees with Judaism and Islam both of which of course honor Jesus – but as a mere religious genius, not as the Christ or as God. Christian faith on the other hand holds emphatically that Jesus is God, that he is indeed the expected Christ (Messiah). Without those beliefs, you’re simply not a Christian.”

As I said, I had other ideas, but bit my tongue.

However, here’s what I wanted to say in response (but thankfully did not):

Jesus is not God

Following the great Jesuit theologian, Roger Haight, I’ve come to believe that Jesus is not God. Instead, I believe that God is Jesus.

The distinction is not merely semantic. Saying that “Jesus is God” presumes that we know what the term “God” means. But that term, of course, has always been entirely problematic. What exactly is content? Answers to that query are legendarily diverse.

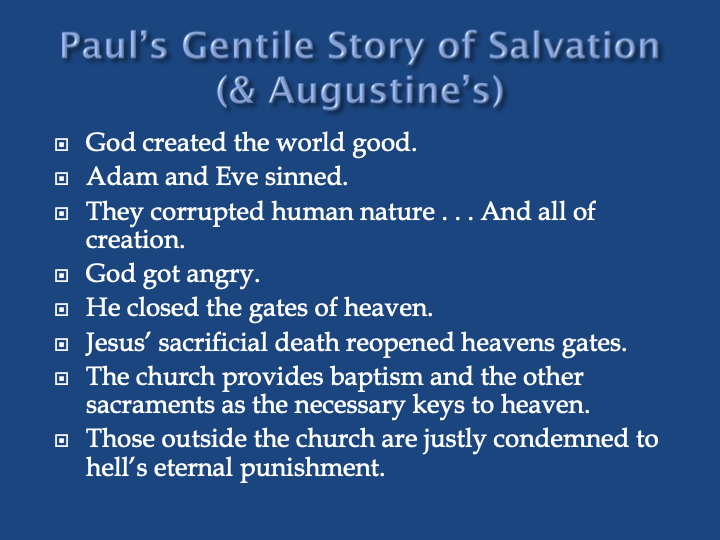

The problem is not only perennial, but in the case of Jesus is compounded by the ironic fact that the identification of Jesus as “God” took place under the aegis of the Roman Empire at the Council of Nicaea in 325. The irony stemmed from the fact that the Council was summoned by the Constantine, the emperor of Rome which had executed the prophet Jesus as an insurgent.

So, Constantine’s own problem was how to transform a rebel against Rome into a God (Deus was the Latin term) not only acceptable to, but supportive of his empire. His conundrum was how to transform Jesus into the son of a God whom worshippers of Zeus could understand.

[By the way, I hope you can see the significance of the similarity in terms Deus and Zeus. Its single consonant variation suggests that the Romans (who knew nothing of the Jewish God, Yahweh) couldn’t help but transform God into a thunder-bold throwing Zeus and Jesus into Zeus’ favorite son Apollo. In practice, no other understandings were possible for them!]

With all of this in mind, remember that Nicaea’s mandate was to answer questions like the following about the identity of Jesus:

- Was he simply a man, a prophet?

- Was he simply a god?

- Was he a man who became a god?

- Was he a god pretending to be a man?

In Constantine’s 4th century, there were “heresies” that represented each of these viewpoints.

But Nicaea’s answer to such questions was different. It stated that: Jesus was a divine being who was fully Deus/Zeus and fully man as well. The Council however left it for future theologians to explain exactly how that combination was possible.

[In my opinion, no one ever successfully did that. Marcus Borg, I think, came closest by holding that Jesus was fully human before his “resurrection” (however we might interpret that term) and fully God afterwards.]

In any case, throughout history Christians themselves have in practice resolved the fully God/fully human dilemma by emphasizing Jesus’ God dimension while neglecting almost entirely his humanity. Practically speaking, Christians have never truly endorsed Jesus’ humanity.

God Is Jesus

And that’s where the importance of holding that “God is Jesus” surfaces. On the one hand, the formulation recognizes the problematic nature of the term “God.” On the other, it resolves the dilemma by pointing to the Jesus of history to reveal the meaning of the term Deus. Look at the human Jesus, it says, and you’ll better understand the meaning of the word God.

And what do we find when we look at Jesus while bracketing official understandings of God as Zeus and Jesus as Apollo? The answer is entirely surprising and turns official theologies on their heads.

As revealed in Jesus, God shows up as the champion not of imperial majesties, but of slaves escaped from those same imperial majesties. More specifically, God’s embodiment (incarnation) is found in a man actually oppressed, not championed by empire. He is a peasant, the son of an unwed teenage mother, a refugee in Egypt, an enemy of the religious establishment, the leader of a poor people’s movement, a victim of torture and of capital punishment.

According to Christian faith, that’s who Jesus is; that’s who God is – found in the poor, the oppressed, in the torture chamber, on death row. . .

The fact that God chose to reveal God’s self as such is what is meant by the Bible’s “preferential option for the poor.”

Jesus is the Christ

All of this is intimately linked with my church friend’s insistence that Jesus is the Christ, the messiah. Here too we must remember that “Christ” is not a Roman term; it is entirely Jewish and has specific Jewish meaning impossible to understand apart from its cultural context.

As Jesus-scholar, Reza Aslan, reminds us, the term “Christ” had one meaning and one meaning only for Jews: the Christ was (1) a descendent of Judah’s King David who would (2) reestablish David’s kingdom (3) in a once again sovereign state. And reestablishing sovereignty necessarily meant disestablishing Rome’s kingdom which occupied 1st century Palestine where Jesus lived.

Of course, the Romans understood that. Consequently, they executed Jesus precisely as an insurgent – along with the untold others in the same historical period who made the same messianic claim. Such was the point of the titulus, “King of the Jews” that the Roman procurator, Pontius Pilate insisted be displayed over Jesus’ head as he hung dying on his cross – the instrument of torture and death reserved for insurgents against the Roman empire (John 19:22). The titulus proclaimed the charges against the executed. Jesus’ crime was proclaiming himself “King of the Jews.”

So, historically speaking, claiming that Jesus is the Christ or messiah is a highly political statement. It signifies belief in Jesus as the quintessential opponent of empire and its inevitable oppression of God’s chosen – the poor and oppressed.

Conclusion

I’m glad I didn’t try to say all of that at last night’s meeting. Still, I’m happy for the evocation of such thoughts by my brother in faith at our Talmadge Hill Community Church.

It all reminded me of what I first learned at a memorable lecture by Passionist scripture scholar, Barnabas Ahern back in 1965 (when I was just 25 years old). Ahern’s topic was the historical Jesus. He inspired me to confront the fact that christians (myself included) tend to believe with all our hearts that Jesus is God, while at the same time paying only lip service to Jesus’ humanity. Ever since then, I resolved to avoid that mistake myself.

In fact, I was so impressed by what Fr. Ahern said that the very next day I wrote out from memory the scholar’s entire talk which has since then played a central role in driving me to internalize modern scripture scholarship about the humanity of the historical Jesus.

It has led me to Roger Haight’s formulation that Jesus is not God, but God is Jesus.

With Reza Aslan’s help, I’ve also come to grasp the revolutionary meaning the terms “Christ” and “Messiah” must have had for 1st century Jews. Then writers such as Marcus Borg have helped me understand the post-resurrection process by which the human Jesus himself appropriated his divine nature – human before his resurrection, divine afterwards.

And that entire sequence of lessons has immeasurably enriched my own faith and enabled me to share their insights.

Thank you, my brothers and teachers Barnabas, Roger, Reza and Marcus.