Ever since Chicago’s Robert Prevost became Pope Leo XIV, I’ve held back from judging the direction of his papacy. When people asked what I thought, I’d say, “I’m slow to comment. He hasn’t yet tipped his hand.”

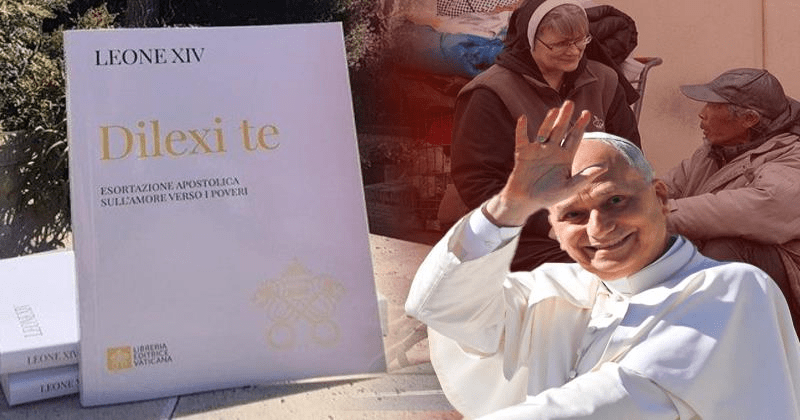

Now, with the publication of the apostolic exhortation Dilexi Te, the cards are finally on the table. Though written by Pope Francis before his death, Pope Leo has fully endorsed and expanded it—embracing it as co-author and carrying forward its message with enthusiasm.

As a liberation theologian, I find this development deeply encouraging. Dilexi Te is a clear affirmation of liberation theology (LT)—which I define as “reflection on the following of Christ from the viewpoint of the poor and oppressed, committed to escaping their poverty and oppression.”

This essay will (1) review what liberation theology is, (2) explain why it so threatens Christian fundamentalists, and (3) show how Dilexi Te embodies its spirit.

Liberation Theology

Liberation theology reflects on Christian faith through the lived experiences of the poor and oppressed. Unlike Christian fundamentalism, it aligns with modern biblical scholarship while remaining accessible to ordinary people, many of them illiterate.

Following the Second Vatican Council (1962–65), liberation theology swept across the Global South—especially Latin America—where the Church turned decisively toward the poor. Small Bible study groups became the heart of parish life. Reading Scripture together, peasants and workers discovered their own struggles mirrored in those of the Hebrews oppressed by Egyptian, Assyrian, Babylonian, Greek, and Roman empires.

Most powerfully, they recognized themselves in Jesus of Nazareth: not white, but brown-skinned; not privileged, but working-class; the son of an unwed teenage mother, homeless at birth, a political refugee in Egypt, a friend of prostitutes and outcasts. He was marginalized by his religious community and executed by imperial authorities as a supposed terrorist.

The U.S. Reaction

Such readings of Scripture awakened the poor to the causes of their oppression—and infuriated the empires profiting from it. The United States, long dominant over its former colonies, perceived liberation theology as a national security threat.

What followed was, in Noam Chomsky’s words, “the first religious war of the twenty-first century”: a U.S.-backed campaign against the Latin American Church. Thousands of priests, nuns, catechists, union organizers, teachers, and social workers were murdered in Argentina, Brazil, Nicaragua, El Salvador, and elsewhere during the 1960s–80s.

Simultaneously, Washington funded fundamentalist televangelists such as Jimmy Swaggart, Jim and Tammy Bakker—and later, figures like Charlie Kirk—to counter liberation theology with “old-time religion.” Their broadcasts, bankrolled by U.S. dollars, saturated Latin America’s barrios, favelas, and poblaciones.

Unlike liberation theology, fundamentalism endorsed empire, patriarchy, white supremacy, and xenophobia. It rejected modern biblical scholarship—especially the historical studies that, ironically, reached many of the same conclusions as liberation theology.

For a time, these tactics succeeded. The CIA and U.S. military boasted of having defeated liberation theology. Christianity, in the public imagination, came to mean not liberation but obedience—focused on heaven and hell, nationalism, and protection of the imperial status quo.

Then Came Francis and Leo

That narrative began to change with the rise of Pope Francis and, now, Pope Leo XIV. Both hail from Latin America, where liberation theology was born anew. Pope Leo’s Peru, in fact, is the homeland of Gustavo Gutiérrez, the movement’s founder.

Francis, an Argentinian, initially distrusted liberation theology because of its use of Marxist social analysis. But over time, he came to embrace its core insight: God’s “preferential option for the poor.” He restored theologians like Gutiérrez—silenced under Pope Benedict XVI—to full standing within the Church.

As Joseph Ratzinger, head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Benedict had authored a cautious 1984 critique, Instruction on Certain Aspects of the Theology of Liberation. Even then, he conceded that the biblical God does indeed side with the poor—acknowledging that this preference is central to the Judeo-Christian tradition.

What troubled Ratzinger was liberation theology’s use of Marxist analysis. Because Marx was an atheist, he reasoned, any theology drawing on his work must be suspect. That argument was, at best, strained.

The Theology of Dilexi Te

Pope Leo’s Dilexi Te moves beyond such debates. It traces the theme of God’s love for the poor—from the liberation of Hebrew slaves in Egypt to its culmination in Jesus the Christ.

In Scripture’s only account of the Last Judgment, Jesus identifies completely with the marginalized:

“I was hungry and you gave me food; thirsty and you gave me drink; a stranger and you welcomed me; naked and you clothed me; sick and you cared for me; in prison and you visited me.” (Matthew 25: 35-40)

This, Leo explains, reveals where God is most fully present today: among the poor, the sick, the imprisoned, the immigrant, and the worker. It was to them that Jesus dedicated his mission:

“The Spirit of the Lord is upon me … he has anointed me to proclaim good news to the poor … to set the oppressed free.” (Luke 4: 18-19)

Pope Leo highlights a long lineage of Christian figures who embodied this vision—Saints Lawrence, Ambrose, Ignatius of Antioch, Justin, Chrysostom, Augustine, Benedict, Francis of Assisi, and in modern times, Mother Teresa and Saint Oscar Romero, the patron of liberation theology.

In Chapter Four, Leo draws attention to what some call “the best-kept secret of the Catholic Church”: its social doctrine. He recalls Rerum Novarum (Leo XIII’s defense of workers’ rights), John XXIII’s call for Vatican II, and that council’s mission to make the Church resemble “her Lord more than worldly powers.” Vatican II, he reminds us, urged concrete global commitment to eradicating poverty.

Leo also revisits the Latin American Bishops’ Conferences at Medellín (1968) and Puebla (1979), where the region’s bishops openly endorsed liberation theology. And strikingly, he quotes from Ratzinger’s 1984 document—not its condemnations, but the passages affirming the biblical foundation of God’s preferential option for the poor.

Conclusion

At a moment when the revolutionary heart of the Judeo-Christian tradition has been domesticated by figures like Charlie Kirk, Dilexi Te reawakens the Church’s original message: another Christianity is possible.

It is a faith that liberates rather than enslaves; that sides with the poor, the nonwhite, the oppressed, the immigrant, the refugee, and the imprisoned. It recalls Jesus the worker and outsider—and the God who dwells among those who suffer.

Thank you, Pope Leo, for reviving this liberating gospel. And thank you, Pope Francis, for lighting the path that made it possible.