Readings for the Sixth Sunday in Ordinary Time: Sirach 15:15-20; Psalm 119; 1 Corinthians 2:6-10; Matthew 5:17-37

Let me say it straight out: the Epstein affair is not primarily about sex. It is about law. It is about whether the commandments — and the legal systems supposedly derived from them — apply equally to everyone.

For decades, Jeffrey Epstein moved among billionaires, politicians, royalty, financiers, academics, and cultural elites. His crimes were known. Complaints were made. Investigations occurred. Yet he received an extraordinary plea deal. Associates remain shielded. Documents remain sealed. Networks remain largely untouched.

Meanwhile, poor defendants fill prisons for far lesser crimes – and in the case of immigrants and asylum seekers, for no crimes at all. Petty theft, drug possession, probation violations, and “illegal” border crossings — these are prosecuted with relentless enforcement of law.

If you want a relevant commentary on such two-tiered systems of “justice,” look no further than today’s liturgical readings. They are explosive in their contemporary application.

Sirach: God Commands No Injustice

Start with Sirach 15: 15-20. There the book’s author says: “If you choose, you can keep the commandments… He has set before you fire and water… life and death.”

At first glance, that sounds like individual moral exhortation. Choose good. Avoid evil. But Sirach adds something devastating: “No one does he command to act unjustly; to none does he give license to sin.”

That line destroys every attempt to sanctify unjust systems like ours. I mean in the United States, injustice is routinely protected by law. After all, Epstein’s plea deal in 2008 was legal. The shielding of his powerful associates has been legal. Non-disclosure agreements are legal. Sealed records are legal.

But Sirach says God commands no injustice.

If the law functions to shield predators when they are rich and well-connected while punishing the poor with mechanical severity, then the issue is not simply moral failure. It is structural perversion.

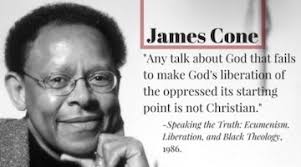

Liberation theology (i.e. non-literalist biblical interpretation supported by modern scripture scholarship) reminds us that “choice” is structured. The poor do not choose within the same field of protection as billionaires. There, fire and water are not distributed evenly. Life and death are not equally accessible.

The commandment is not merely “Don’t sin.” The deeper question is: Does the legal order reflect God’s refusal to legalize injustice?

Psalm 119: Blessed Are Those Who Follow the Law

Now look at today’s responsorial psalm. It’s refrain proclaims: “Blessed are they who follow the law of the Lord.”

But what is the law for?

As José Porfirio Miranda and Norman Gottwald argue, the Decalogue emerged not as abstract piety but as social protection. It arose among people resisting royal systems that accumulated land, wealth, and power in elite hands.

Both theologians remind us that biblical law was a shield for subsistence households. “You shall not steal” originally meant: the powerful may not confiscate the livelihood of the vulnerable. “You shall not covet” meant desire backed by power must be restrained.

In that light, now ask the uncomfortable question: when billionaires operate in networks of mutual protection and the law seems reluctant to expose them fully, is that still Torah? Or is it what the prophets called “corruption at the gate?”

Psalm 119 blesses those who follow God’s law — not those who manipulate civil law to protect privilege.

Paul: The Wisdom of the Rulers

In the same spirit of Sirach and Psalm 119, Paul speaks of “a wisdom not of this age, nor of the rulers of this age… who are passing away.” He also adds something chilling: “None of the rulers of this age understood this; for if they had, they would not have crucified the Lord of glory.”

The cross was a legal execution. It was state-sanctioned. It was justified under Roman law and enabled by religious authority.

That’s Paul’s point.

The rulers always believe their system is rational and necessary. Franz Hinkelammert reminds us that ruling ideologies present themselves as inevitable. Markets are inevitable. Elite networks are inevitable. Certain people are untouchable.

When the Epstein affair reveals how proximity to wealth and power appears to blunt accountability, we are witnessing what Paul calls “the wisdom of this age.” A wisdom that protects itself.

The rulers crucified Jesus legally. Legality is not the same as justice.

Jesus: Fulfilling the Law by Protecting the Vulnerable

In Matthew’s Gospel, Jesus declares:

“I have not come to abolish the law but to fulfill it.”

Then he radicalizes it. “You have heard it said, ‘You shall not kill.’ But I say to you, whoever humiliates…”

Jesus’ point is that dehumanization precedes violence. When victims are dismissed because they lack status, when their testimony is doubted because they are young, poor, or socially marginal, contempt is already at work.

“You have heard it said… You shall not commit adultery. But I say to you, whoever looks with lust…”

Could these words be more pertinent to the Epstein Affair? In a world where wealthy men are allowed to treat vulnerable underage girls and women as property, lust backed by power means coercion. Jesus targets the interior logic of such domination.

His teaching on divorce does the same thing. It sides with the economically vulnerable spouse. Legal permission did not equal justice.

Notice the pattern: every intensification of the commandment in today’s readings closes loopholes that allow the powerful to exploit the weak.

That is fulfillment of the law. If a legal system permits exploitation through influence, money, and secrecy, it has not fulfilled the law. It has hollowed it out.

Two Systems

The Epstein affair is not an anomaly. It is a revelation.

It reveals what liberation theology has long argued: sin is social as well as personal. Structures can be sinful. Systems can crucify.

When poor defendants encounter swift prosecution while elite networks encounter delay, protection, and opacity, we are not witnessing isolated moral failure. We are witnessing two systems.

Sirach sets before us life and death. The death-dealing system is one where law bends upward. The life-giving system is one where law protects the vulnerable first:

- “Blessed are they who follow the law of the Lord.”

- Blessed are those who refuse to equate legality with justice.

- Blessed are those who demand that commandments function as protection for the powerless.

- Blessed are those who see through the “wisdom” of powerful elites

Jesus did not abolish the commandments. He sharpened them until they pierced hypocrisy.

Before us remain fire and water. The question is not whether we personally avoid wrongdoing.

The question is whether we will accept a system where justice is negotiated by wealth — or insist that the law once again become what it was meant to be: protection and good news for the poor.