I recently found myself in conversation with a young activist—brilliant, earnest, morally serious—who made a claim that was both understandable and unsettling. Young people, he said, simply don’t want to hear from old people like me, especially old white men. We’ve had our turn. We made a mess. And whatever we call “wisdom,” grounded in our long lives and accumulated experience, feels to them less like insight and more like obstruction.

I understood immediately why he would feel that way. My generation was born during the Great Depression and its aftermath; the boomers who followed presided over imperial wars, environmental devastation, runaway capitalism, and the hollowing out of democratic institutions. Zoomers have every reason to be suspicious of elders who lecture them about patience, realism, or incremental change. The house is on fire. Who wants to hear a sermon about proper etiquette?

And yet, something about the conversation troubled me—not because I felt personally dismissed, but because of the assumptions beneath the dismissal. In particular, the identification of “young people” with young Americans struck me as dangerously parochial. Outside the United States, especially in the Global South, students and young intellectuals are often strikingly comprehensive in their critical thinking. They do not imagine that wisdom expires with age, nor that critique began with TikTok.

Across Latin America, Africa, and parts of Europe, young activists routinely engage figures who are not only old, but long dead: Marx, Engels, Gramsci; Frantz Fanon, Simone de Beauvoir, W.E.B. Du Bois, Mary Daly, and Malcolm X. They read these thinkers not out of antiquarian curiosity, but because the structures those thinkers analyzed—capital, empire, race, class—remain very much alive. Ideas endure because oppression endures.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the tradition known as liberation theology.

Liberation Theology

Liberation theology is often caricatured in the United States as a quaint Latin American experiment, a left-wing theological fad that peaked in the 1980s and was later disciplined by Rome. That caricature misses the point entirely. Liberation theology is not primarily a set of doctrines; it is a method. More precisely, it is a disciplined form of critical thinking rooted in the lived experience of the poor. (In this connection, see my book, The Magic Glasses of Critical Thinking: seeing through alternative fact and fake news.)

At its core lies a deceptively simple question: From whose point of view are we interpreting reality? Classical theology asked what God is like. Liberation theology asks where God is to be found. And its answer—radical then, still radical now—is among the poor, the exploited, the colonized, and the discarded.

This shift has enormous epistemological consequences. It means that theology is not done from the armchair, nor from the pulpit alone, but from within history’s conflicts. Truth is not neutral. Knowledge is not innocent. Every analysis reflects interests, whether acknowledged or denied.

This is why liberation theologians insist on what they call praxis: reflection and action in constant dialogue. Ideas are tested not by elegance but by their consequences. Do they liberate, or do they legitimate domination?

That is critical thinking in its most rigorous form.

Beyond the American Youth Bubble

In Latin America, thinkers such as Gustavo Gutiérrez, Elsa Tamez, Leonardo Boff, Jon Sobrino, and figures like Franz Hinkelammert, Enrique Dussel, Paulo Freire, and Helio Gallardo pushed this method far beyond church walls. They integrated history, economics, philosophy, pedagogy, and political theory into theological reflection. They read the Bible alongside dependency theory and Marxist political economy, not because Marx was a prophet (he was!), but because capitalism is a religion—and a deadly one.

Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed remains one of the most influential works of critical pedagogy worldwide. Its central insight—that education is never neutral, that it either domesticates or liberates—could easily be applied to theology, media, or political discourse. What Freire called “conscientization” is nothing other than the awakening of class consciousness.

Contrast this with much of American youth culture, where “critical thinking” is often reduced to identity signaling or stylistic rebellion, easily co-opted by market logic. The phenomenon of Charlie Kirk and similar figures is instructive here. Kirk’s appeal to college students is not an aberration; it is a symptom. Young people are starving for meaning, for narrative coherence, for moral seriousness. Into that vacuum rush slick, biblically uninformed ideologues like Kirk who weaponize Scripture in service of hierarchy and exclusion.

The Bible as Popular Philosophy

For millions of Americans, the Bible remains the primary source of moral reasoning—and often of historical understanding as well. This is frequently mocked by secular intellectuals, but mockery is a luxury we can no longer afford. The Bible functions in the United States as a form of popular philosophy. People may know little about economics, geopolitics, or climate science, but they believe they know what the Bible says.

And what they believe it says shapes their views on Israel and Palestine, abortion, feminism, sexuality, immigration, and race.

The tragedy is not that the Bible matters, but that it has been systematically stripped of its prophetic core and repackaged as an ideological weapon. White, patriarchal, misogynistic, anti-gay, xenophobic, and racist forces have successfully co-opted a tradition that is, at its heart, a sustained critique of empire, wealth accumulation, and religious hypocrisy.

This is not accidental. Empires have always sought divine sanction.

Yeshua of Nazareth & Class Consciousness

What liberation theology insists upon—and what American Christianity has largely forgotten—is that the Judeo-Christian tradition is saturated with class consciousness. From the Exodus narrative to the prophets, from the Magnificat to the Beatitudes, the Bible relentlessly sides with the poor against the powerful.

Yeshua of Nazareth did not preach generic love or abstract spirituality. He announced “good news to the poor,” warned the rich, overturned tables, and was executed by the state as a political threat. His message was not “be nice,” but “another world is possible—and this one is under judgment.”

Liberation theology takes that judgment seriously. It refuses to spiritualize away material suffering or postpone justice to the afterlife. Salvation is not escape from history but transformation of it.

To say this today is not to indulge in nostalgia. It is to recover a critical tradition capable of resisting the authoritarian, nationalist, and theocratic currents now surging globally.

The Need for More God Talk, Not Less

Here is where my disagreement with my young interlocutor becomes sharpest. The problem is not that there is too much God talk. The problem is that there is too little serious God talk.

When theology abdicates the public square, it leaves moral language to demagogues. When progressives abandon religious discourse, they surrender one of the most powerful symbolic systems shaping mass consciousness. You cannot defeat biblical nationalism by ignoring the Bible.

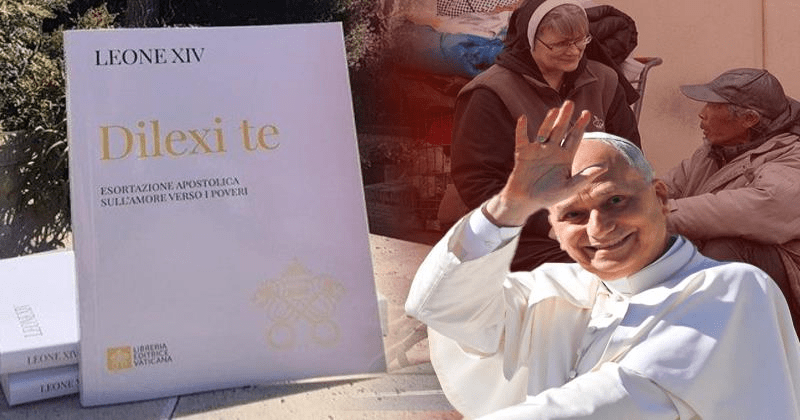

Liberation theology offers an alternative: God talk grounded in history, class analysis, and the lived experience of the oppressed. It exposes false universals. It unmasks ideology. It insists that faith, like reason, must answer to reality.

This is not theology for clerics alone. It is a way of thinking—rigorous, suspicious of power, attentive to suffering—that belongs at the heart of any emancipatory project.

Old Voices, Living Questions

Perhaps young Americans are right to be wary of elders who speak as if experience itself confers authority. It does not. But it is equally short-sighted to assume that age disqualifies insight, or that the past has nothing left to teach us.

Outside the United States, young people know better. They read old texts because the structures those texts analyze persist. They mine ancient traditions because myths and stories carry truths that statistics alone cannot.

Liberation theology stands at precisely this intersection: ancient scripture and modern critique, myth and materialism, faith and class struggle. It reminds us that critical thinking did not begin with social media, and that wisdom does not belong to any generation.

If we are serious about liberation—real liberation, not branding—then we must reclaim every tool that helps us see clearly. Theology, done rightly, is one of them.

Not because God solves our problems.

But because the question of God forces us to ask, relentlessly: Who benefits? Who suffers? And whose side are we on?